The New York City teachers' strike of 1968 was a months-long confrontation between the new community-controlled school board in the largely black Ocean Hill–Brownsville neighborhoods of Brooklyn and New York City's United Federation of Teachers. It began with a one day walkout in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville school district. It escalated to a citywide strike in September of that year, shutting down the public schools for a total of 36 days and increasing racial tensions between blacks and Jews.

Thousands of New York City teachers went on strike in 1968 when the school board of the neighborhood, which is now two separate neighborhoods, fired nineteen teachers and administrators without notice. The newly created school district, in a heavily black neighborhood, was an experiment in community control over schools—those dismissed were almost all Jewish.

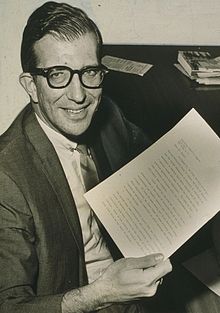

The United Federation of Teachers (UFT), led by Albert Shanker, demanded the teachers' reinstatement and accused the community-controlled school board of anti-semitism. At the start of the school year in September 1968, the UFT held a strike that shut down New York City's public schools for nearly two months, leaving a million students without schools to attend.

The strike pitted community against union, highlighting a conflict between local rights to self-determination and teachers' universal rights as workers.[1] Although the school district itself was quite small, the outcome of its experiment had great significance because of its potential to alter the entire educational system—in New York City and elsewhere. As one historian wrote in 1972: "If these seemingly simple acts had not been such a serious threat to the system, it would be unlikely that they would produce such a strong and immediate response."[2]

- ^ Green, Philip (Summer 1970). "Decentralization, Community Control, and Revolution: Reflections on Ocean Hill-Brownsville". The Massachusetts Review. 11 (3). The Massachusetts Review, Inc.: 415–441. JSTOR 25088003.

- ^ Gittell, Marilyn (October 1972). "Decentralization and Citizen Participation in Education". Public Administration Review. 32 (Curriculum Essays on Citizens, Politics, and Administration in Urban Neighborhoods): 670–686. doi:10.2307/975232. JSTOR 975232.

How fundamental was this effort at institutional change? At a minimum it attacked the structure on the delivery of services and the allocation of resources. At a maximum it potentially challenged the institutionalization of racism in America. It seriously challenged the "merit" civil service system which had become the main- stay of the American bureaucratic structure. It raised the issue of accountability of public service professionals and pointed to the distribution of power in the system and the inequities of the policy output of that structure. In a short three years, the Ocean Hill-Brownsville districts and IS 201, through such seemingly simple acts as hiring their own principals, allocating larger sums of money for the use of paraprofessionals, transfer- ring or dismissing teachers, and adopting a variety of new educational programs, had brought all of these issues into the forefront of the political arena.