| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

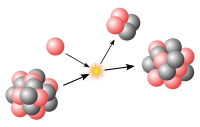

In nuclear physics, ab initio methods seek to describe the atomic nucleus from the bottom up by solving the non-relativistic Schrödinger equation for all constituent nucleons and the forces between them. This is done either exactly for very light nuclei (up to four nucleons) or by employing certain well-controlled approximations for heavier nuclei. Ab initio methods constitute a more fundamental approach compared to e.g. the nuclear shell model. Recent progress has enabled ab initio treatment of heavier nuclei such as nickel.[1]

A significant challenge in the ab initio treatment stems from the complexities of the inter-nucleon interaction. The strong nuclear force is believed to emerge from the strong interaction described by quantum chromodynamics (QCD), but QCD is non-perturbative in the low-energy regime relevant to nuclear physics. This makes the direct use of QCD for the description of the inter-nucleon interactions very difficult (see lattice QCD), and a model must be used instead. The most sophisticated models available are based on chiral effective field theory. This effective field theory (EFT) includes all interactions compatible with the symmetries of QCD, ordered by the size of their contributions. The degrees of freedom in this theory are nucleons and pions, as opposed to quarks and gluons as in QCD. The effective theory contains parameters called low-energy constants, which can be determined from scattering data.[1][2]

Chiral EFT implies the existence of many-body forces, most notably the three-nucleon interaction which is known to be an essential ingredient in the nuclear many-body problem.[1][2]

After arriving at a Hamiltonian (based on chiral EFT or other models) one must solve the Schrödinger equation where is the many-body wavefunction of the A nucleons in the nucleus. Various ab initio methods have been devised to numerically find solutions to this equation:

- Green's function Monte Carlo (GFMC)[3]

- No-core shell model (NCSM)[4]

- Coupled cluster (CC)[5]

- Self-consistent Green's function (SCGF)[6]

- In-medium similarity renormalization group (IM-SRG)[7]

- ^ a b Machleidt, R.; Entem, D.R. (2011). "Chiral effective field theory and nuclear forces". Physics Reports. 503 (1): 1–75. arXiv:1105.2919. Bibcode:2011PhR...503....1M. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2011.02.001. S2CID 118434586.

- ^ Pieper, S. C.; Wiringa, R. B. (2001). "Quantum Monte Carlo calculations of light nuclei". Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science. 51: 53–90. arXiv:nucl-th/0103005. Bibcode:2001ARNPS..51...53P. doi:10.1146/annurev.nucl.51.101701.132506. S2CID 18124819.

- ^ Barrett, B.R.; Navrátil, P.; Vary, J.P. (2013). "Ab initio no core shell model". Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics. 69: 131–181. Bibcode:2013PrPNP..69..131B. doi:10.1016/j.ppnp.2012.10.003.

- ^ Hagen, G.; Papenbrock, T.; Hjorth-Jensen, M.; Dean, D. J. (2014). "Coupled-cluster computations of atomic nuclei". Reports on Progress in Physics. 77 (9): 096302. arXiv:1312.7872. Bibcode:2014RPPh...77i6302H. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/77/9/096302. PMID 25222372. S2CID 10626343.

- ^ Cipollone, A.; Barbieri, C.; Navrátil, P. (2013). "Isotopic Chains Around Oxygen from Evolved Chiral Two- and Three-Nucleon Interactions". Physical Review Letters. 111 (6): 062501. arXiv:1303.4900. Bibcode:2013PhRvL.111f2501C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.062501. PMID 23971568. S2CID 2198329.

- ^ Hergert, H.; Binder, S.; Calci, A.; Langhammer, J.; Roth, R. (2013). "Ab Initio Calculations of Even Oxygen Isotopes with Chiral Two-Plus-Three-Nucleon Interactions". Physical Review Letters. 110 (24): 242501. arXiv:1302.7294. Bibcode:2013PhRvL.110x2501H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.242501. PMID 25165916. S2CID 5501714.