This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2019) |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | ACh |

| License data | |

| ATC code | |

| Physiological data | |

| Source tissues | motor neurons, parasympathetic nervous system, brain |

| Target tissues | skeletal muscles, brain, many other organs |

| Receptors | nicotinic, muscarinic |

| Agonists | nicotine, muscarine, cholinesterase inhibitors |

| Antagonists | tubocurarine, atropine |

| Precursor | choline, acetyl-CoA |

| Biosynthesis | choline acetyltransferase |

| Metabolism | acetylcholinesterase |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| E number | E1001(i) (additional chemicals) |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.118 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

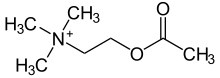

| Formula | C7H16NO2 |

| Molar mass | 146.210 g·mol−1 |

Acetylcholine (ACh) is an organic compound that functions in the brain and body of many types of animals (including humans) as a neurotransmitter.[1] Its name is derived from its chemical structure: it is an ester of acetic acid and choline.[2] Parts in the body that use or are affected by acetylcholine are referred to as cholinergic.

Acetylcholine is the neurotransmitter used at the neuromuscular junction—in other words, it is the chemical that motor neurons of the nervous system release in order to activate muscles. This property means that drugs that affect cholinergic systems can have very dangerous effects ranging from paralysis to convulsions. Acetylcholine is also a neurotransmitter in the autonomic nervous system, both as an internal transmitter for both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous system, and as the final product released by the parasympathetic nervous system.[1] Acetylcholine is the primary neurotransmitter of the parasympathetic nervous system.[2][3]

In the brain, acetylcholine functions as a neurotransmitter and as a neuromodulator. The brain contains a number of cholinergic areas, each with distinct functions; such as playing an important role in arousal, attention, memory and motivation.[4] Acetylcholine has also been found in cells of non-neural origins as well as microbes. Recently, enzymes related to its synthesis, degradation and cellular uptake have been traced back to early origins of unicellular eukaryotes.[5] The protist pathogens Acanthamoeba spp. have shown evidence of the presence of ACh, which provides growth and proliferative signals via a membrane-located M1-muscarinic receptor homolog.[6]

Partly because of acetylcholine's muscle-activating function, but also because of its functions in the autonomic nervous system and brain, many important drugs exert their effects by altering cholinergic transmission. Numerous venoms and toxins produced by plants, animals, and bacteria, as well as chemical nerve agents such as sarin, cause harm by inactivating or hyperactivating muscles through their influences on the neuromuscular junction. Drugs that act on muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, such as atropine, can be poisonous in large quantities, but in smaller doses they are commonly used to treat certain heart conditions and eye problems.[7][8] Scopolamine, or diphenhydramine, which also act mainly on muscarinic receptors in an inhibitory fashion in the brain (especially the M1 receptor) can cause delirium, hallucinations, and amnesia through receptor antagonism at these sites. So far as of 2016, only the M1 receptor subtype has been implicated in anticholinergic delirium.[9] The addictive qualities of nicotine are derived from its effects on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain.

- ^ a b Tiwari P, Dwivedi S, Singh MP, Mishra R, Chandy A (October 2012). "Basic and modern concepts on cholinergic receptor: A review". Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease. 3 (5): 413–420. doi:10.1016/S2222-1808(13)60094-8. PMC 4027320.

- ^ a b Sam C, Bordoni B (2023). "Physiology, Acetylcholine". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32491757. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ Lott EL, Jones EB (June 2019). "Cholinergic Toxicity". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30969605.

- ^ Kapalka GM (2010). "Substances Involved in Neurotransmission". Nutritional and Herbal Therapies for Children and Adolescents. Elsevier. pp. 71–99. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-374927-7.00004-2. ISBN 978-0-12-374927-7.

- ^ Baig AM, Rana Z, Tariq S, Lalani S, Ahmad HR (March 2018). "Traced on the Timeline: Discovery of Acetylcholine and the Components of the Human Cholinergic System in a Primitive Unicellular Eukaryote Acanthamoeba spp". ACS Chem Neurosci. 9 (3): 494–504. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00254. PMID 29058403.

- ^ Baig AM, Ahmad HR (June 2017). "Evidence of a M1-muscarinic GPCR homolog in unicellular eukaryotes: featuring Acanthamoeba spp bioinformatics 3D-modelling and experimentations". J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 37 (3): 267–275. doi:10.1080/10799893.2016.1217884. PMID 27601178. S2CID 5234123.

- ^ Avetisov SE, Fisenko VP, Zhuravlev AS, Avetisov KS (2018). "Применение атропина для контроля прогрессирования миопии" [Atropine use for the prevention of myopia progression]. Vestnik Oftalmologii (in Russian). 134 (4): 84–90. doi:10.17116/oftalma201813404184. PMID 30166516.

- ^ Smulyan H (November 2018). "The Beat Goes On: The Story of Five Ageless Cardiac Drugs". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 356 (5): 441–450. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2018.04.011. PMID 30055757.

- ^ Dawson AH, Buckley NA (March 2016). "Pharmacological management of anticholinergic delirium - theory, evidence and practice". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 81 (3): 516–524. doi:10.1111/bcp.12839. PMC 4767198. PMID 26589572.

Delirium is only associated with the antagonism of post‐synaptic M1 receptors and to date other receptor subtypes have not been implicated