Adropin is a protein encoded by the energy homeostasis-associated gene ENHO in humans[5] and is highly conserved across mammals.[6]

The biological role of adropin was first described in mice by Andrew Butler's team. They identified it as a protein hormone (hepatokine) secreted from the liver, playing a role in obesity and energy homeostasis. The name "Adropin" is derived from the Latin words "aduro" (to set fire to) and "pinguis" (fat).[7] Adropin is produced in various tissues, including the liver, brain, heart, and gastrointestinal tract.[8]

In animals, adropin regulates carbohydrate and lipid metabolism[9] and influences endothelial function.[10][11] Its expression in the liver is controlled by feeding status, macronutrient content,[9] as well as by the biological clock.[12] Liver adropin is upregulated by estrogen[13] via the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα).[14]

In humans, lower levels of circulating adropin are linked to several medical conditions, including the metabolic syndrome, obesity, and inflammatory bowel disease.[15] and inflammatory bowel disease.[16] The brain exhibits the highest levels of adropin expression,[17] In the brain, adropin has been shown to have a potential protective role against neurological disease,[18] where it may play a protective role against neurological diseases, brain aging, cognitive decline, and acute ischemia.[19][20] as well as following acute ischemia.[21]

The orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR19 has been proposed as a receptor for adropin.[22][23]

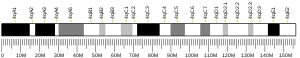

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000168913 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000028445 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "ENHO Gene - GeneCards | ENHO Protein | ENHO Antibody". www.genecards.org.

- ^ "ortholog_gene_375704[group] - Gene - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ Kumar KG, Trevaskis JL, Lam DD, Sutton GM, Koza RA, Chouljenko VN, et al. (December 2008). "Identification of adropin as a secreted factor linking dietary macronutrient intake with energy homeostasis and lipid metabolism". Cell Metabolism. 8 (6): 468–481. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2008.10.011. PMC 2746325. PMID 19041763.

- ^ Jasaszwili M, Billert M, Strowski MZ, Nowak KW, Skrzypski M (January 2020). "Adropin as A Fat-Burning Hormone with Multiple Functions-Review of a Decade of Research". Molecules. 25 (3): 549. doi:10.3390/molecules25030549. PMC 7036858. PMID 32012786.

- ^ a b Banerjee S, Ghoshal S, Stevens JR, McCommis KS, Gao S, Castro-Sepulveda M, et al. (October 2020). "Hepatocyte expression of the micropeptide adropin regulates the liver fasting response and is enhanced by caloric restriction". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 295 (40): 13753–13768. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA120.014381. PMC 7535914. PMID 32727846.

- ^ Lovren F, Pan Y, Quan A, Singh KK, Shukla PC, Gupta M, et al. (September 2010). "Adropin is a novel regulator of endothelial function". Circulation. 122 (11 Suppl): S185–S192. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.931782. PMID 20837912. S2CID 798093.

- ^ Jurrissen TJ, Ramirez-Perez FI, Cabral-Amador FJ, Soares RN, Pettit-Mee RJ, Betancourt-Cortes EE, et al. (November 2022). "Role of adropin in arterial stiffening associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes". American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 323 (5): H879–H891. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00385.2022. hdl:10355/94230. PMC 9602697. PMID 36083795. S2CID 252160224.

- ^ Kolben Y, Weksler-Zangen S, Ilan Y (February 2021). "Adropin as a potential mediator of the metabolic system-autonomic nervous system-chronobiology axis: Implementing a personalized signature-based platform for chronotherapy". Obesity Reviews. 22 (2): e13108. doi:10.1111/obr.13108. PMID 32720402. S2CID 220841405.

- ^ Stokar J, Gurt I, Cohen-Kfir E, Yakubovsky O, Hallak N, Benyamini H, et al. (June 2022). "Hepatic adropin is regulated by estrogen and contributes to adverse metabolic phenotypes in ovariectomized mice". Molecular Metabolism. 60: 101482. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101482. PMC 9044006. PMID 35364299.

- ^ Meda C, Dolce A, Vegeto E, Maggi A, Della Torre S (August 2022). "ERα-Dependent Regulation of Adropin Predicts Sex Differences in Liver Homeostasis during High-Fat Diet". Nutrients. 14 (16): 3262. doi:10.3390/nu14163262. PMC 9416503. PMID 36014766.

- ^ Soltani S, Kolahdouz-Mohammadi R, Aydin S, Yosaee S, Clark CC, Abdollahi S (March 2022). "Circulating levels of adropin and overweight/obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies". Hormones. 21 (1): 15–22. doi:10.1007/s42000-021-00331-0. PMID 34897581. S2CID 245119139.

- ^ Brnić D, Martinovic D, Zivkovic PM, Tokic D, Tadin Hadjina I, Rusic D, et al. (June 2020). "Serum adropin levels are reduced in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 9264. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.9264B. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-66254-9. PMC 7283308. PMID 32518265.

- ^ "Tissue expression of ENHO - Summary - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ Gunraj RE, Yang C, Liu L, Larochelle J, Candelario-Jalil E (March 2023). "Protective roles of adropin in neurological disease". American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 324 (3): C674–C678. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00318.2022. PMC 10027081. PMID 36717106.

- ^ Banerjee S, Ghoshal S, Girardet C, DeMars KM, Yang C, Niehoff ML, et al. (August 2021). "Adropin correlates with aging-related neuropathology in humans and improves cognitive function in aging mice". npj Aging and Mechanisms of Disease. 7 (1): 23. doi:10.1038/s41514-021-00076-5. PMC 8405681. PMID 34462439.

- ^ Aggarwal G, Morley JE, Vellas B, Nguyen AD, Butler AA (May 2023). "Low circulating adropin concentrations predict increased risk of cognitive decline in community-dwelling older adults". GeroScience. 46 (1): 897–911. doi:10.1007/s11357-023-00824-3. PMC 10828274. PMID 37233882.

- ^ Yang C, Liu L, Lavayen BP, Larochelle J, Gunraj RE, Butler AA, et al. (January 2023). "Therapeutic Benefits of Adropin in Aged Mice After Transient Ischemic Stroke via Reduction of Blood-Brain Barrier Damage". Stroke. 54 (1): 234–244. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.039628. PMC 9780180. PMID 36305313. S2CID 253184087.

- ^ Stein LM, Yosten GL, Samson WK (March 2016). "Adropin acts in brain to inhibit water drinking: potential interaction with the orphan G protein-coupled receptor, GPR19". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 310 (6): R476–R480. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00511.2015. PMC 4867374. PMID 26739651.

- ^ Devine RN, Butler A, Chrivia J, Vagner J, Arnatt CK (June 2023). "Probing Adropin-Gpr19 Interactions and Signal Transduction". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 385 (S3): 430. doi:10.1124/jpet.122.550630. ISSN 0022-3565.