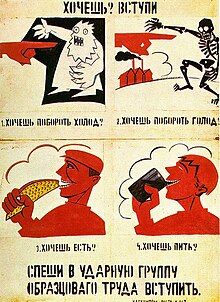

"1. You want to overcome cold?

2. You want to overcome hunger?

3. You want to eat?

4. You want to drink?

Hasten to join shock brigades of exemplary labor!"

Agitprop (/ˈædʒɪtprɒp/;[1][2][3] from Russian: агитпроп, romanized: agitpróp, portmanteau of agitatsiya, "agitation" and propaganda, "propaganda")[4] refers to an intentional, vigorous promulgation of ideas. The term originated in the Soviet Union where it referred to popular media, such as literature, plays, pamphlets, films, and other art forms, with an explicitly political message in favor of communism.[5]

The term originated in the Soviet Union as a shortened name for the Department for Agitation and Propaganda (отдел агитации и пропаганды, otdel agitatsii i propagandy), which was part of the central and regional committees of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[6] Within the party apparatus, both agitation (work among people who were not Communists) and propaganda (political work among party members) were the responsibility of the agitpropotdel, or APPO. Its head was a member of the MK secretariat, although they ranked second to the head of the orgraspredotdel.[7] Typically Russian agitprop explained the ideology and policies of the Communist Party and attempted to persuade the general public to support and join the party and share its ideals. Agitprop was also used for dissemination of information and knowledge to the people, like new methods of agriculture. After the October Revolution of 1917, an agitprop train toured the country, with artists and actors performing simple plays and broadcasting propaganda.[8] It had a printing press on board the train to allow posters to be reproduced and thrown out of the windows as it passed through villages.[9] The first head of the Propaganda and Agitation Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (b) was Evgeny Preobrazhensky.[10]

It gave rise to agitprop theatre, a highly politicized theatre that originated in 1920s Europe and spread to the United States; the plays of Bertolt Brecht are a notable example.[11] Russian agitprop theater was noted for its cardboard characters of perfect virtue and complete evil, and its coarse ridicule.[12] Gradually, the term agitprop came to describe any kind of highly politicized art.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ "agitprop". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ "agitprop(n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (July 11, 2002). "agitprop". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "Agitprop". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ Merridale, Catherine (1990). Moscow Politics and the Rise of Stalin. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 142. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-21042-8_8. ISBN 978-1-349-21044-2.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Agitprop Train". YouTube. 2007-06-15. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ Paul A. Smith, On Political War, p. 124, National Defense University Press, 1989

- ^ "Departments, commissions and institutions of the Central Committee of RCP (b) - VKP (b) - CPSU". Archived from the original on 2019-05-25.

- ^ Richard Bodek (1998) "Proletarian Performance in Weimar Berlin: Agitprop, Chorus, and Brecht", ISBN 1-57113-126-4

- ^ Richard Pipes, Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime, p. 303, ISBN 978-0-394-50242-7