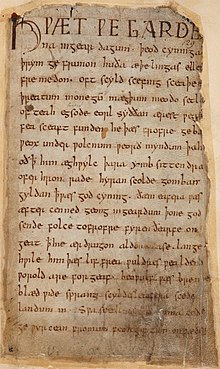

In prosody, alliterative verse is a form of verse that uses alliteration as the principal device to indicate the underlying metrical structure, as opposed to other devices such as rhyme.[1] The most commonly studied traditions of alliterative verse are those found in the oldest literature of the Germanic languages, where scholars use the term 'alliterative poetry' rather broadly to indicate a tradition which not only shares alliteration as its primary ornament but also certain metrical characteristics.[2] The Old English epic Beowulf, as well as most other Old English poetry, the Old High German Muspilli, the Old Saxon Heliand, the Old Norse Poetic Edda, and many Middle English poems such as Piers Plowman, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Layamon's Brut and the Alliterative Morte Arthur all use alliterative verse.[3][4][5][6]

While alliteration is common in many poetic traditions, it is 'relatively infrequent' as a structured characteristic of poetic form.[7]: 41 However, structural alliteration appears in a variety of poetic traditions, including Old Irish, Welsh, Somali and Mongol poetry.[8][9][10][11] The extensive use of alliteration in the so-called Kalevala meter, or runic song, of the Finnic languages provides a close comparison, and may derive directly from Germanic-language alliterative verse.[12]

Unlike in other Germanic languages, where alliterative verse has largely fallen out of use (except for deliberate revivals, like Richard Wagner's 19th-century German Ring Cycle[13]), alliteration has remained a vital feature of Icelandic poetry.[14] After the 14th Century, Icelandic alliterative poetry mostly consisted of rímur,[15] a verse form which combines alliteration with rhyme. The most common alliterative ríma form is ferskeytt, a kind of quatrain.[16] Examples of rimur include Disneyrímur by Þórarinn Eldjárn, ''Unndórs rímur'' by an anonymous author, and the rimur transformed to post-rock anthems by Sigur Ros.[17] From 19th century poets like Jonas Halgrimsson[18] to 21st-century poets like Valdimar Tómasson, alliteration has remained a prominent feature of modern Icelandic literature, though contemporary Icelandic poets vary in their adherence to traditional forms.[19]

By the early 19th century, alliterative verse in Finnish was largely restricted to traditional, largely rural folksongs, until Elias Lönnrot and his compatriots collected them and published them as the Kalevala, which rapidly became the national epic of Finland and contributed to the Finnish independence movement.[20] This led to poems in Kalevala meter becoming a significant element in Finnish literature[21][22] and popular culture.[23]

Alliterative verse has also been revived in Modern English.[24][25] Many modern authors include alliterative verse among their compositions, including Poul Anderson, W.H. Auden, Fred Chappell, Richard Eberhart, John Heath-Stubbs, C. Day-Lewis, C. S. Lewis, Ezra Pound, John Myers Myers, Patrick Rothfuss, L. Sprague de Camp, J. R. R. Tolkien and Richard Wilbur.[26][25] Modern English alliterative verse covers a wide range of styles and forms, ranging from poems in strict Old English or Old Norse meters, to highly alliterative free verse that uses strong-stress alliteration to connect adjacent phrases without strictly linking alliteration to line structure.[27] While alliterative verse is relatively popular in the speculative fiction (specifically, the speculative poetry) community,[28][29] and is regularly featured at events sponsored by the Society for Creative Anachronism,[28][30] it also appears in poetry collections published by a wide range of practicing poets.[31]

- ^ Hogan, Patrick Colm (1997). "Literary Universals". Poetics Today. 18 (2): 223–249. doi:10.2307/1773433. JSTOR 1773433.

- ^ Goering, N. (2016). The linguistic elements of Old Germanic metre: phonology, metrical theory, and the development of alliterative verse (Thesis). OCLC 1063660140.[page needed]

- ^ The Poetic Edda. 1962. doi:10.7560/764996. ISBN 978-0-292-74791-3.[page needed]

- ^ Russom, Geoffrey (1998). "Old Saxon alliterative verse". Beowulf and Old Germanic Metre. pp. 136–170. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511582981.011. ISBN 978-0-521-59340-3.

- ^ Sommer, Herbert W. (October 1960). "The Muspilli-Apocalypse". The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory. 35 (3): 157–163. doi:10.1080/19306962.1960.11787011.

- ^ Cable, Thomas (1991). The English Alliterative Tradition. doi:10.9783/9781512803853. ISBN 978-1-5128-0385-3.

- ^ Frog, Mr. (2019). "The Finnic Tetrameter – A Creolization of Poetic Form?". Studia Metrica et Poetica. 6 (1): 20–78. doi:10.12697/smp.2019.6.1.02. S2CID 198517325.

- ^ Travis, James (April 1942). "The Relations between Early Celtic and Early Germanic Alliteration". The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory. 17 (2): 99–105. doi:10.1080/19306962.1942.11786083.

- ^ Salisbury, Eurig (2017). "Cynghanedd". The Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature in Britain. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/9781118396957.wbemlb495. ISBN 978-1-118-39698-8.

- ^ Kara, György (2011). "Alliteration in Mongol Poetry". Alliteration in Culture. pp. 156–179. doi:10.1057/9780230305878_11. ISBN 978-1-349-31301-3.

- ^ Orwin, Martin (2011). "Alliteration in Somali Poetry". Alliteration in Culture. pp. 219–230. doi:10.1057/9780230305878_14. ISBN 978-1-349-31301-3.

- ^ Frog (29 August 2019). "The Finnic Tetrameter – A Creolization of Poetic Form?". Studia Metrica et Poetica. 6 (1): 20–78. doi:10.12697/smp.2019.6.1.02. S2CID 198517325.

- ^ Gupta, Rahul (September 2014). 'The Tale of the Tribe': The Twentieth-Century Alliterative Revival (Thesis). pp. 7–8.

- ^ Adalsteinsson, Ragnar Ingi (2014). Traditions and Continuities: Alliteration in Old and Modern Icelandic Verse. University of Iceland Press. ISBN 978-9935-23-036-2.

- ^ Ross, Margaret Clunies (2005). A History of Old Norse Poetry and Poetics. DS Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84384-279-8.[page needed]

- ^ Vésteinn Ólason, 'Old Icelandic Poetry', in A History of Icelandic Literature, ed. by Daisy Nejmann, Histories of Scandinavian Literature, 5 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006), pp. 1-63 (pp. 55-59).

- ^ "Rímur EP (2001) - Sigur Rós with Steindór Andersen - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ "Jónas Hallgrímsson: Selected Poetry and Prose". digicoll.library.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ Árnason, Kristján (2011). "Alliteration in Iceland: From the Edda to Modern Verse and Pop Lyrics". Alliteration in Culture. pp. 123–140. doi:10.1057/9780230305878_9. ISBN 978-1-349-31301-3.

- ^ Wilson, William A. (1975). "The 'Kalevala' and Finnish Politics". Journal of the Folklore Institute. 12 (2/3): 131–155. doi:10.2307/3813922. JSTOR 3813922.

- ^ Simonsuuri, Kirsti (1989). "From Orality to Modernity: Aspects of Finnish Poetry in the Twentieth Century". World Literature Today. 63 (1): 52–54. doi:10.2307/40145048. JSTOR 40145048.

- ^ Alhoniemi, Pirkko; Binham, Philip (1985). "Modern Finnish Literature from Kalevala and Kanteletar Sources". World Literature Today. 59 (2): 229. doi:10.2307/40141460. JSTOR 40141460.

- ^ Doesburg, Charlotte (June 2021). "Of heroes, maidens and squirrels: Reimagining traditional Finnish folk poetry in metal lyrics". Metal Music Studies. 7 (2): 317–333. doi:10.1386/mms_00051_1. S2CID 237812043.

- ^ Wise, Dennis Wilson (June 2021). "Poul Anderson and the American Alliterative Revival". Extrapolation. 62 (2): 157–180. doi:10.3828/extr.2021.9. S2CID 242510584.

- ^ a b Wilson Wise, Dennis (2021). "Antiquarianism Underground: The Twentieth-century Alliterative Revival in American Genre Poetry". Studies in the Fantastic. 11 (1): 22–54. doi:10.1353/sif.2021.0001. S2CID 238935463.

- ^ "Published Authors of Alliterative Verse". Forgotten Ground Regained. Retrieved 2023-11-21.

- ^ "Styles and Themes: Trends in Modern Alliterative Verse". Forgotten Ground Regained. Retrieved 2023-11-28.

- ^ a b Wise, Dennis, ed. (2023-12-15). Speculative Poetry and the Modern Alliterative Revival: A Critical Anthology. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-1-68393-329-8.

- ^ "The Speculative Fiction Community". Forgotten Ground Regained. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ^ "The Society for Creative Anachronism: Sponsors of Alliterative Verse". Forgotten Ground Regained. Retrieved 2023-11-24.

- ^ "Collections: Anthologies that Contain Alliterative Verse". Forgotten Ground Regained. Retrieved 2023-11-24.