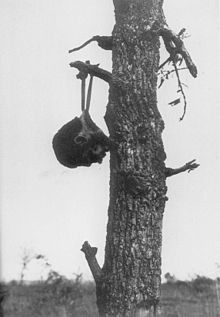

During World War II, some members of the United States military mutilated dead Japanese service personnel in the Pacific theater. The mutilation of Japanese service personnel included the taking of body parts as "war souvenirs" and "war trophies". Teeth and skulls were the most commonly taken "trophies", although other body parts were also collected.

The phenomenon of "trophy-taking" was widespread enough that discussion of it featured prominently in magazines and newspapers. Franklin Roosevelt himself was reportedly given a gift of a letter-opener made of a Japanese soldier's arm by U.S. Representative Francis E. Walter in 1944, which Roosevelt later ordered to be returned, calling for its proper burial.[3][4] The news was also widely reported to the Japanese public, where the Americans were portrayed as "deranged, primitive, racist and inhuman". This, compounded by a previous Life magazine picture of a young woman with a skull trophy, was reprinted in the Japanese media and presented as a symbol of American barbarism, causing national shock and outrage.[5][6]

The behavior was officially prohibited by the U.S. military, which issued additional guidance as early as 1942 condemning it specifically.[7] Nonetheless, the behavior was infrequently prosecuted[citation needed] and it continued throughout the war in the Pacific theater, and has resulted in continued discoveries of "trophy skulls" of Japanese combatants in American possession, as well as American and Japanese efforts to repatriate the remains of the Japanese dead.

- ^ Roeder, George H. Jr. (Fall 1995). "Missing on the home front". National Forum. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016.

- ^ Lewis A. Erenberg; Susan E. Hirsch (1996). The War in American Culture: Society and Consciousness During World War II. University of Chicago Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0226215112.

- ^ Weingartner 1992, p. 65.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 825.

- ^ Harrison 2006, p. 833.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

dickeywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Harrison 2006, p. 827.