This article possibly contains original research. (March 2012) |

Augustan literature (sometimes referred to misleadingly as Georgian literature) is a style of British literature produced during the reigns of Queen Anne, King George I, and George II in the first half of the 18th century and ending in the 1740s, with the deaths of Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift, in 1744 and 1745, respectively. It was a literary epoch that featured the rapid development of the novel, an explosion in satire, the mutation of drama from political satire into melodrama and an evolution toward poetry of personal exploration. In philosophy, it was an age increasingly dominated by empiricism, while in the writings of political economy, it marked the evolution of mercantilism as a formal philosophy, the development of capitalism and the triumph of trade.

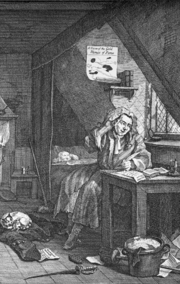

The chronological boundary points of the era are generally vague, largely since the label's origin in contemporary 18th-century criticism has made it a shorthand designation for a somewhat nebulous age of satire. Samuel Johnson, whose famous A Dictionary of the English Language was published in 1755, is also "to some extent" associated with the Augustan period.[1] The new Augustan period exhibited exceptionally bold political writings in all genres, with the satires of the age marked by an arch, ironic pose, full of nuance and a superficial air of dignified calm that hid sharp criticisms beneath.

While the period is generally known for its adoption of highly regulated and stylized literary forms, some of the concerns of writers of this period, with the emotions, folk and a self-conscious model of authorship, foreshadowed the preoccupations of the later Romantic era. In general, philosophy, politics and literature underwent a turn away from older courtly concerns towards something closer to a modern sensibility.

- ^ J. A. Cuddon,A Dictionary of Literary Terms, London: Penguin, 1999, p. 61.