| Auto-brewery syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Gut fermentation syndrome, Endogenous ethanol fermentation |

| |

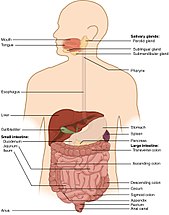

| Digestive system | |

Auto-brewery syndrome (ABS) (also known as gut fermentation syndrome, endogenous ethanol fermentation or drunkenness disease) is a condition characterized by the fermentation of ingested carbohydrates in the gastrointestinal tract of the body caused by bacteria or fungi.[1] ABS is a rare medical condition in which intoxicating quantities of ethanol are produced through endogenous fermentation within the digestive system.[2] The organisms responsible for ABS include various yeasts and bacteria, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, S. boulardii, Candida albicans, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, Kluyveromyces marxianus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterococcus faecium.[1] These organisms use lactic acid fermentation or mixed acid fermentation pathways to produce an ethanol end product.[3] The ethanol generated from these pathways is absorbed in the small intestine, causing an increase in blood alcohol concentrations that produce the effects of intoxication without the consumption of alcohol.[4]

Researchers speculate the underlying causes of ABS are related to prolonged antibiotic use,[5] poor nutrition and/or diets high in carbohydrates,[6] and to pre-existing conditions such as diabetes and genetic variations that result in improper liver enzyme activity.[7] In the last case, decreased activity of aldehyde dehydrogenase can result in accumulation of ethanol in the gut, leading to fermentation.[7] Any of these conditions, alone or in combination, could cause ABS, and result in dysbiosis of the microbiome.[5]

Another variant, urinary auto-brewery syndrome, is when the fermentation occurs in the urinary bladder rather than the gut.

Claims of endogenous fermentation have been attempted as a defense against drunk driving charges, some of which have been successful, but the condition is so rare and under-researched they are currently not substantiated by available studies.[7]

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

:1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Kaji H, Asanuma Y, Yahara O, Shibue H, Hisamura M, Saito N, et al. (1984). "Intragastrointestinal alcohol fermentation syndrome: report of two cases and review of the literature". Journal of the Forensic Science Society. 24 (5): 461–71. doi:10.1016/S0015-7368(84)72325-5. PMID 6520589.

- ^ Fayemiwo SA, Adegboro B (2013-11-20). "Gut fermentation syndrome". African Journal of Clinical and Experimental Microbiology. 15 (1): 48–50. doi:10.4314/ajcem.v15i1.8. ISSN 1595-689X.

- ^ Hafez EM, Hamad MA, Fouad M, Abdel-Lateff A (May 2017). "Auto-brewery syndrome: Ethanol pseudo-toxicity in diabetic and hepatic patients". Human & Experimental Toxicology. 36 (5): 445–450. Bibcode:2017HETox..36..445H. doi:10.1177/0960327116661400. PMID 27492480. S2CID 3666503.

- ^ a b Cordell BJ, Kanodia A, Miller GK (January 2019). "Case-Control Research Study of Auto-Brewery Syndrome". Global Advances in Health and Medicine. 8: 2164956119837566. doi:10.1177/2164956119837566. PMC 6475837. PMID 31037230.

- ^ Saverimuttu J, Malik F, Arulthasan M, Wickremesinghe P (October 2019). "A Case of Auto-brewery Syndrome Treated with Micafungin". Cureus. 11 (10): e5904. doi:10.7759/cureus.5904. PMC 6853272. PMID 31777691.

- ^ a b c Logan BK, Jones AW (July 2000). "Endogenous ethanol 'auto-brewery syndrome' as a drunk-driving defence challenge". Medicine, Science, and the Law. 40 (3): 206–15. doi:10.1177/002580240004000304. PMID 10976182. S2CID 6926029.