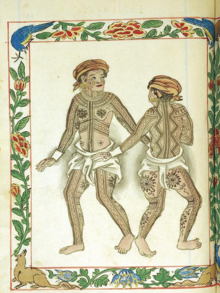

Batok, batek, patik, batik, or buri, among other names, are general terms for indigenous tattoos of the Philippines.[1] Tattooing on both sexes was practiced by almost all ethnic groups of the Philippine Islands during the pre-colonial era. Like other Austronesian groups, these tattoos were made traditionally with hafted tools tapped with a length of wood (called the "mallet"). Each ethnic group had specific terms and designs for tattoos, which are also often the same designs used in other art forms and decorations such as pottery and weaving. Tattoos range from being restricted only to certain parts of the body to covering the entire body. Tattoos were symbols of tribal identity and kinship, as well as bravery, beauty, and social or wealth status.[2][3][4][5]

Tattooing traditions were mostly lost as Filipinos were converted to Christianity during the Spanish colonial era. Tattooing was also lost in some groups (like the Tagalog and the Moro people) shortly before the colonial period due to their (then recent) conversion to Islam. It survived until around the 19th to the mid-20th centuries in more remote areas of the Philippines, but also fell out of practice due to modernization and western influence. Today, it is a highly endangered tradition and only survives among some members of the Cordilleran peoples of the Luzon highlands,[2] some Lumad people of the Mindanao highlands,[6] and the Sulodnon people of the Panay highlands.[4][7][8]

- ^ Wilcken, Lane. "What is Batok?". Lane Wilcken. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Wilcken, Lane (2010). Filipino Tattoos: Ancient to Modern. Schiffer. ISBN 9780764336027.

- ^ Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo University Press. pp. 20–27. ISBN 9789715501354.

- ^ a b Salvador-Amores, Analyn. Burik: Tattoos of the Ibaloy Mummies of Benguet, North Luzon, Philippines. In Ancient Ink: The Archaeology of Tattooing, edited by Lars Krutak and Aaron Deter-Wolf, pp. 37–55. University of Washington Press, Seattle, Washington.

- ^ "The Beautiful History and Symbolism of Philippine Tattoo Culture". Aswang Project. May 4, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Ragragio, Andrea Malaya M.; Paluga, Myfel D. (August 22, 2019). "An Ethnography of Pantaron Manobo Tattooing (Pangotoeb): Towards a Heuristic Schema in Understanding Manobo Indigenous Tattoos". Southeast Asian Studies. 8 (2): 259–294. doi:10.20495/seas.8.2_259. S2CID 202261104.

- ^ Jocano, F. Landa (1958). "The Sulod: A Mountain People In Central Panay, Philippines". Philippine Studies. 6 (4): 401–436. JSTOR 42720408.

- ^ Carpio, Audrey (April 7, 2023). "Meet the 106-Year-Old Woman Keeping an Ancient Filipino Tattooing Tradition Alive". Vogue. Retrieved October 25, 2024.