Benjamin Franklin | |

|---|---|

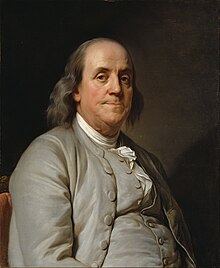

Portrait by Joseph Duplessis, 1778 | |

| 6th President of Pennsylvania | |

| In office October 18, 1785 – November 5, 1788 | |

| Vice President | |

| Preceded by | John Dickinson |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Mifflin |

| United States Minister to Sweden | |

| In office September 28, 1782 – April 3, 1783 | |

| Appointed by | Congress of the Confederation |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Jonathan Russell |

| United States Minister to France | |

| In office March 23, 1779 – May 17, 1785 | |

| Appointed by | Continental Congress |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| 1st United States Postmaster General | |

| In office July 26, 1775 – November 7, 1776 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Richard Bache |

| Delegate from Pennsylvania to the Second Continental Congress | |

| In office May 1775 – October 1776 | |

| Postmaster General of British America | |

| In office August 10, 1753 – January 31, 1774 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | vacant |

| Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly | |

| In office May 1764 – October 1764 | |

| Preceded by | Isaac Norris |

| Succeeded by | Isaac Norris |

| 1st President of the University of Pennsylvania | |

| In office 1749–1754 | |

| Succeeded by | William Smith |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 17, 1706 [O.S. January 6, 1705][Note 1] Boston, Massachusetts Bay, English America |

| Died | April 17, 1790 (aged 84) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Christ Church Burial Ground, Philadelphia |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Parents | |

| Education | Boston Latin School |

| Signature |  |

Benjamin Franklin (January 17, 1706 [O.S. January 6, 1705][Note 1] – April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a leading writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and political philosopher.[1] Among the most influential intellectuals of his time, Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States; a drafter and signer of the Declaration of Independence; and the first postmaster general.[2]

Franklin became a successful newspaper editor and printer in Philadelphia, the leading city in the colonies, publishing the Pennsylvania Gazette at age 23.[3] He became wealthy publishing this and Poor Richard's Almanack, which he wrote under the pseudonym "Richard Saunders".[4] After 1767, he was associated with the Pennsylvania Chronicle, a newspaper known for its revolutionary sentiments and criticisms of the policies of the British Parliament and the Crown.[5] He pioneered and was the first president of the Academy and College of Philadelphia, which opened in 1751 and later became the University of Pennsylvania. He organized and was the first secretary of the American Philosophical Society and was elected its president in 1769. He was appointed deputy postmaster-general for the British colonies in 1753,[6] which enabled him to set up the first national communications network.

He was active in community affairs and colonial and state politics, as well as national and international affairs. Franklin became a hero in America when, as an agent in London for several colonies, he spearheaded the repeal of the unpopular Stamp Act by the British Parliament. An accomplished diplomat, he was widely admired as the first U.S. ambassador to France and was a major figure in the development of positive Franco–American relations. His efforts proved vital in securing French aid for the American Revolution. From 1785 to 1788, he served as President of Pennsylvania. At some points in his life, he owned slaves and ran "for sale" ads for slaves in his newspaper, but by the late 1750s, he began arguing against slavery, became an active abolitionist, and promoted the education and integration of African Americans into U.S. society.[7]

As a scientist, his studies of electricity made him a major figure in the American Enlightenment and the history of physics. He also charted and named the Gulf Stream current. His numerous important inventions include the lightning rod, bifocals, glass harmonica and the Franklin stove.[8] He founded many civic organizations, including the Library Company, Philadelphia's first fire department,[9] and the University of Pennsylvania.[10] Franklin earned the title of "The First American" for his early and indefatigable campaigning for colonial unity. He was the only person to sign the Declaration of Independence, Treaty of Paris, peace with Britain and the Constitution. Foundational in defining the American ethos, Franklin has been called "the most accomplished American of his age and the most influential in inventing the type of society America would become".[11]

His life and legacy of scientific and political achievement, and his status as one of America's most influential Founding Fathers, have seen Franklin honored for more than two centuries after his death on the $100 bill and in the names of warships, many towns and counties, educational institutions and corporations, as well as in numerous cultural references and a portrait in the Oval Office. His more than 30,000 letters and documents have been collected in The Papers of Benjamin Franklin. Anne Robert Jacques Turgot said of him: "Eripuit fulmen cœlo, mox sceptra tyrannis" ("He snatched lightning from the sky and the scepter from tyrants").[12]

Cite error: There are <ref group=Note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=Note}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021

- ^ Morris, Richard B. (1973). Seven Who Shaped Our Destiny: The Founding Fathers as Revolutionaries. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 1, 5–30. ISBN 978-0-06-090454-8.

- ^ Brands, H.W. (2010). The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. 390. ISBN 978-0-307-75494-3.

- ^ Goodrich, Charles A. (1829). Lives of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence. W. Reed & Company. p. 267. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ "William Goddard and the Constitutional Post". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ^ "Benjamin Franklin, Postmaster General" (PDF). United States Postal Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ Nash, 2006, pp. 618–638.

- ^ Franklin Institute, Essay

- ^ Burt, Nathaniel (1999). The Perennial Philadelphians: The Anatomy of an American Aristocracy. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-8122-1693-6.

- ^ Isaacson, 2004, p. [page needed]

- ^ Isaacson, 2004, pp. 491–492.

- ^ "To the Genius of Franklin". Philadelphia Museum of Art.