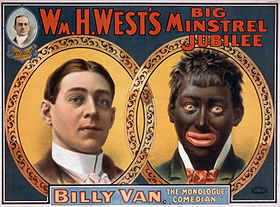

Blackface is the practice of performers using burnt cork, shoe polish, or theatrical makeup to portray a caricature of black people on stage or in entertainment. Scholarship on the origins or definition of blackface vary with some taking a global perspective that includes European culture and Western colonialism.[1] Scholars with this wider view may date the practice of blackface to as early as Medieval Europe's mystery plays when bitumen and coal were used to darken the skin of white performers portraying demons, devils, and damned souls. Still others date the practice to English Renaissance theatre, in works such as William Shakespeare's Othello.

However, some scholars see blackface as a specific practice limited to American culture that began in the minstrel show; a performance art that originated in the United States in the early 19th century and which contained its own performance practices unique to the American stage. Scholars taking this point of view see blackface as arising not from a European stage tradition but from the context of class warfare[2] from within the United States, with the American white working poor inventing blackface as a means of expressing their anger over being disenfranchised economically, politically, and socially from middle and upper class White America.

In the United States, the practice of blackface became a popular entertainment during the 19th century into the 20th. It contributed to the spread of racial stereotypes such as "Jim Crow", the "happy-go-lucky darky on the plantation", and "Zip Coon" also known as the "dandified coon".[3][4][2]

By the middle of the 19th century, blackface minstrel shows had become a distinctive American artform, translating formal works such as opera into popular terms for a general audience.[5] Although minstrelsy began with white performers, by the 1840s there were also many all-black cast minstrel shows touring the United States in blackface, as well as black entertainers performing in shows with predominately white casts in blackface. Some of the most successful and prominent minstrel show performers, composers and playwrights were themselves black, such as: Bert Williams, Bob Cole, and J. Rosamond Johnson.

Early in the 20th century, blackface branched off from the minstrel show and became a form of entertainment in its own right,[6] including Tom Shows, parodying abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. In the United States, blackface declined in popularity from the 1940s, with performances dotting the cultural landscape into the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.[7] It was generally considered highly offensive, disrespectful, and racist by the late 20th century,[8] but the practice (or similar-looking ones) was exported to other countries.[9][10]

- ^ "Blackface: The Birth of An American Stereotype". National Museum of African American History and Culture. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- ^ a b Rehin, George F. (December 1975). "Harlequin Jim Crow: Continuity and Convergence in Blackface Clowning". The Journal of Popular Culture. 9 (3): 682–701. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1975.0903_682.x. ProQuest 1297376766.

- ^ For the "darky"/"coon" distinction see, for example, note 34 on p. 167 of Edward Marx and Laura E. Franey's annotated edition of Yone Noguchi, The American Diary of a Japanese Girl, Temple University Press, 2007, ISBN 1592135552. See also Lewis A. Erenberg (1984), Steppin' Out: New York Nightlife and the Transformation of American Culture, 1890–1930, University of Chicago Press, p. 73, ISBN 0226215156. For more on the "darky" stereotype, see J. Ronald Green (2000), Straight Lick: The Cinema of Oscar Micheaux, Indiana University Press, pp. 134, 206, ISBN 0253337534; p. 151 of the same work also alludes to the specific "coon" archetype.

- ^ Nowatzki, Robert (2006). "Paddy Jumps Jim Crow: Irish-Americans and Blackface Minstrelsy". Éire-Ireland. 41 (3): 162–184. doi:10.1353/eir.2007.0010. S2CID 161886074. Project MUSE 207996.

- ^ Mahar, William John (1999). Behind the Burnt Cork Mask: Early Blackface Minstrelsy and Antebellum American Popular Culture. University of Illinois Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-252-06696-2.

- ^ Sweet, Frank W. (2000). A History of the Minstrel Show. Boxes & Arrows, Incorporated. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-939479-21-4.

- ^ Clark, Alexis. "How the History of Blackface Is Rooted in Racism". History. A&E Television Networks, LLC. 2019.

- ^ Desmond-Harris, Jenée (October 29, 2014). "Don't get what's wrong with blackface? Here's why it's so offensive". Vox.

- ^ Garen, Micah; Carleton, Marie-Helene; Swaab, Justine (November 27, 2019). "Black Pete tradition 'Dutch racism in full display'". Al Jazeera.

Protesters have rallied against the Dutch blackface tradition

- ^ Thelwell, Chinua (2020). Exporting Jim Crow: Blackface Minstrelsy in South Africa and Beyond. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-1-61376-766-5. Project MUSE book 77081.[page needed]