| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

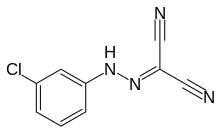

| Preferred IUPAC name

N-(4-Chlorophenyl)carbonohydrazonoyl dicyanide | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.277 |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | CCCP |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C9H5ClN4 | |

| Molar mass | 204.616 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP; also known as [(3-chlorophenyl)hydrazono]malononitrile) is a chemical inhibitor of oxidative phosphorylation. It is a nitrile, hydrazone and protonophore. In general, CCCP causes the gradual destruction of living cells and death of the organism,[1][2] although mild doses inducing partial decoupling have been shown to increase median and maximum lifespan in C. elegans models, suggesting a degree of hormesis.[3][4][5] CCCP causes an uncoupling of the proton gradient that is established during the normal activity of electron carriers in the electron transport chain. The chemical acts essentially as an ionophore and reduces the ability of ATP synthase to function optimally. It is routinely[6] used as an experimental uncoupling agent in cell and molecular biology, particularly in the study of mitophagy,[7] where it was integral in discovering the role of the Parkinson's disease-associated ubiquitin ligase Parkin.[7] Outside of its effects on mitochondria, CCCP may also disrupt lysosomal degradation during autophagy.[7][8]

- ^ J.W. Park; S.Y. Lee; J.Y. Yang; H.W. Rho; B.H. Park; S.N. Lim; J.S. Kim; H.R. Kim (1997). "Effect of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCmCP) on the dimerization of lipoprotein lipase". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Lipids and Lipid Metabolism. 1344 (2): 132–8. doi:10.1016/s0005-2760(96)00146-4. PMID 9030190.

- ^ D. Gášková; B. Brodská; A. Holoubek; K. Sigler (1999). "Factors and processes involved in membrane potential build-up in yeast: diS-C3(3) assay". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 31 (5): 575–584. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(99)00002-3. PMID 10399318.

- ^ Lemire, Bernard D.; Behrendt, Maciej; DeCorby, Adrienne; Gášková, Dana (July 2009). "C. elegans longevity pathways converge to decrease mitochondrial membrane potential". Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 130 (7): 461–465. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2009.05.001. PMID 19442682. S2CID 23043275. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Parkhitko, Andrey A.; Filine, Elizabeth; Mohr, Stephanie E.; Moskalev, Alexey; Perrimon, Norbert (December 2020). "Targeting metabolic pathways for extension of lifespan and healthspan across multiple species". Ageing Research Reviews. 64: 101188. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2020.101188. PMC 9038119. PMID 33031925.

- ^ Bárcena, Clea; Mayoral, Pablo; Quirós, Pedro M. (2018). "Mitohormesis, an Antiaging Paradigm". International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology. 340: 35–77. doi:10.1016/bs.ircmb.2018.05.002. ISBN 9780128157367. PMID 30072093. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Lin, Bo; Liu, Yunfan; Zhang, Xiaoping; Fan, Li; Shu, Yang; Wang, Jianhua (November 10, 2021). "Membrane-Activated Fluorescent Probe for High-Fidelity Imaging of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential". ACS Sensors. 6 (11): 4009–4018. doi:10.1021/acssensors.1c01390. PMID 34757720. S2CID 243988045. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Georgakopoulos, Nikolaos D; Wells, Geoff; Campanella, Michelangelo (2017). "The pharmacological regulation of cellular mitophagy". Nature Chemical Biology. 13 (2): 136–146. doi:10.1038/nchembio.2287. PMID 28103219. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Padman, B.S.; Bach, M.; Lucarelli, G.; Prescott, M.; Ramm, G. (2013). "The protonophore CCCP interferes with lysosomal degradation of autophagic cargo in yeast and mammalian cells". Autophagy. 9 (11): 1862–1875. doi:10.4161/auto.26557. PMID 24150213. S2CID 37257051. Retrieved 24 December 2021.