| Cardiac allograft vasculopathy | |

|---|---|

| |

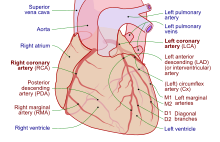

| Coronary arteries | |

| Specialty | Cardiology, angiology |

| Symptoms | None, breathlessness, tiredness[1] |

| Usual onset | After heart transplantation[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Coronary angiography, intravascular ultrasound, dobutamine stress echocardiography, positron emission tomography, CT angiography, biomarkers, endomyocardial biopsy[2] |

| Treatment | Control cardiovascular risk factors, mTOR inhibitors, re-transplantation[1] |

| Medication | Sirolimus, everolimus[1] |

| Prognosis | Progressive[2] |

| Frequency | Around 50% (in 10 years)[2] |

| Deaths | 11-13% of heart transplants one year from surgery[1] |

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV) is a progressive type of coronary artery disease in people who have had a heart transplant.[1] As the donor heart has lost its nerve supply there is typically no chest pain, and CAV is usually detected on routine testing.[2] It may present with symptoms such as tiredness and breathlessness.[2]

It arises when the blood vessels supplying the transplanted heart change in structure.[3] They gradually narrow and restrict its blood flow, subsequently leading to impairment of the heart muscle or sudden death.[4] In addition to the same risk factors for coronary artery disease due to the build up of plaque, CAV is more likely to occur if the donor was older or died from explosive brain death, and if there is cytomegalovirus infection.[2] Its mechanism involves immunological (innate and adaptive) and nonimmunological factors, with distinct features on histological samples of coronary arteries.[2] Other major causes of death following heart transplantation include graft failure, organ rejection and infection.[5]

Diagnosis is by regular follow-up and monitoring of the transplanted heart for early signs of disease.[2] Tests include coronary angiography, intravascular ultrasound, dobutamine stress echocardiography, positron emission tomography, computed tomographic angiography (CT angiography) and several biomarkers.[2]

Statins and aspirin are commenced early after transplantation and on detection of CAV.[2] Medications including sirolimus and everolimus can slow disease progression.[2] A repeat heart transplantation may be required.[6]

CAV affects around half of heart transplant recipients within 10 years.[2] It contributes to the death of 11-13% one year from heart transplantation.[1]

- ^ a b c d e f g Shanmuganathan, Mayooran; Dar, Owais (2020). "73. Complications of heart transplantation". In Raja, Shahzad G. (ed.). Cardiac Surgery: A Complete Guide. Switzerland: Springer. p. 669. ISBN 978-3-030-24176-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Stehlik, Josef; Kobashigawa, Jon; Hunt, Sharon A.; Reichenspurner, Hermann; Kirklin, James K. (2 January 2018). "Honoring 50 Years of Clinical Heart Transplantation in Circulation". Circulation. 137 (1): 71–87. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029753. PMID 29279339.

- ^ Pober, Jordan S; Chih, Sharon; Kobashigawa, Jon; Madsen, Joren C; Tellides, George (3 August 2021). "Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: current review and future research directions". Cardiovascular Research. 117 (13): 2624–2638. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvab259. PMC 8783389. PMID 34343276.

- ^ Elsevier (2010). "New ISHLT Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy Standardized Nomenclature: A Common International Definition Will Benefit Heart Transplant Patients". www.elsevier.com. Elsevier. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ Dipchand, Anne I. (2018-01-02). "Current state of pediatric cardiac transplantation". Annals of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 7 (1): 31–55–55. doi:10.21037/acs.2018.01.07. ISSN 2225-319X. PMC 5827130. PMID 29492382.

- ^ Lee, Michael S.; Tadwalkar, Rigved V.; Fearon, William F.; Kirtane, Ajay J.; Patel, Amisha J.; Patel, Chetan B.; Ali, Ziad; Rao, Sunil V. (2018-12-01). "Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: A review". Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 92 (7): E527–E536. doi:10.1002/ccd.27893. ISSN 1522-726X. PMID 30265435. S2CID 52880607.(subscription required)