| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌsɛfəˈlɛksɪn/ |

| Trade names | Keflex, others |

| Other names | cephalexin, cephalexin (BAN UK), cephalexin (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682733 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | First-generation cephalosporin |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Well absorbed |

| Protein binding | 15% |

| Metabolism | 80% excreted unchanged in urine within 6 hours of administration |

| Elimination half-life | 0.6–1.2 hours[3] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.036.142 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

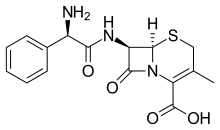

| Formula | C16H17N3O4S |

| Molar mass | 347.39 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 326.8 °C (620.2 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Cefalexin, also spelled cephalexin, is an antibiotic that can treat a number of bacterial infections.[4] It kills gram-positive and some gram-negative bacteria by disrupting the growth of the bacterial cell wall.[4] Cefalexin is a β-lactam antibiotic within the class of first-generation cephalosporins.[4] It works similarly to other agents within this class, including intravenous cefazolin, but can be taken by mouth.[5]

Cefalexin can treat certain bacterial infections, including those of the middle ear, bone and joint, skin, and urinary tract.[4] It may also be used for certain types of pneumonia and strep throat and to prevent bacterial endocarditis.[4] Cefalexin is not effective against infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), most Enterococcus, or Pseudomonas.[4] Like other antibiotics, cefalexin cannot treat viral infections, such as the flu, common cold or acute bronchitis.[4] Cefalexin can be used in those who have mild or moderate allergies to penicillin.[4] However, it is not recommended in those with severe penicillin allergies.[4]

Common side effects include stomach upset and diarrhea.[4] Allergic reactions or infections with Clostridioides difficile, a cause of diarrhea, are also possible.[4] Use during pregnancy or breastfeeding does not appear to be harmful to the fetus.[4][6][7] It can be used in children and those over 65 years of age.[4] Those with kidney problems may require a decrease in dose.[4]

Cefalexin was developed in 1967.[8][9][10] It was first marketed in 1969 under the brand name Keflex.[11][12] It is available as a generic medication.[4][13] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[14] In 2022, it was the 101st most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 6 million prescriptions.[15][16] In Canada, it was the fifth most common antibiotic used in 2013.[17] In Australia, it was one of the top 10 most prescribed medications between 2017 and 2023.[18]

- ^ "Cephalexin Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 28 December 2018. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lexylan PIwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ McEvoy, G.K. (ed.). American Hospital Formulary Service — Drug Information 95. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Hospital Pharmacists, Inc., 1995 (Plus Supplements 1995)., p. 166

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Cephalexin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 1 May 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ Brunton LL (2011). "Chapter 53: Penicillins, Cephalosporins, and Other β-Lactam Antibiotics". Goodman & Gilman's pharmacological basis of therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071624428.

- ^ "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ Jones W (2013). Breastfeeding and Medication. Routledge. p. 227. ISBN 9781136178153. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Hey E, ed. (2007). Neonatal formulary 5 drug use in pregnancy and the first year of life (5th ed.). Blackwell. p. 67. ISBN 9780470750353. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.>

- ^ US patent 3275626, Morin RB, Jackson BG, "Penicillin conversion via sulfoxide", published 1966-09-27, issued 1966-09-27, assigned to Eli Lilly and Co "Espacenet - Bibliographic data". Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ US patent 3507861, Morin RB, Jackson BG, "Certain 3-methyl-cephalosporin compounds", published 1970-04-21, issued 1970-04-21, assigned to Eli Lilly and Co "Espacenet - Bibliographic data". Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ McPherson EM (2007). "Cefalexin". Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). Burlington: Elsevier. p. 915. ISBN 9780815518563. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Ravina E (2011). The evolution of drug discovery : from traditional medicines to modern drugs (1. Aufl. ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 267. ISBN 9783527326693. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Hanlon G, Hodges N (2012). Essential Microbiology for Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Science. Hoboken: Wiley. p. 140. ISBN 9781118432433. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Cephalexin Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Human Antimicrobial Drug Use Report 2012/2013" (PDF). Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). November 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ "Medicines in the health system". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2 July 2024. Retrieved 30 September 2024.