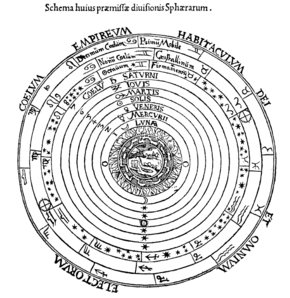

The celestial spheres, or celestial orbs, were the fundamental entities of the cosmological models developed by Plato, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, and others. In these celestial models, the apparent motions of the fixed stars and planets are accounted for by treating them as embedded in rotating spheres made of an aetherial, transparent fifth element (quintessence), like gems set in orbs. Since it was believed that the fixed stars did not change their positions relative to one another, it was argued that they must be on the surface of a single starry sphere.[1]

In modern thought, the orbits of the planets are viewed as the paths of those planets through mostly empty space. Ancient and medieval thinkers, however, considered the celestial orbs to be thick spheres of rarefied matter nested one within the other, each one in complete contact with the sphere above it and the sphere below.[2] When scholars applied Ptolemy's epicycles, they presumed that each planetary sphere was exactly thick enough to accommodate them.[2] By combining this nested sphere model with astronomical observations, scholars calculated what became generally accepted values at the time for the distances to the Sun: about 4 million miles (6.4 million kilometres), to the other planets, and to the edge of the universe: about 73 million miles (117 million kilometres).[3] The nested sphere model's distances to the Sun and planets differ significantly from modern measurements of the distances,[4] and the size of the universe is now known to be inconceivably large and continuously expanding.[5]

Albert Van Helden has suggested that from about 1250 until the 17th century, virtually all educated Europeans were familiar with the Ptolemaic model of "nesting spheres and the cosmic dimensions derived from it".[6] Even following the adoption of Copernicus's heliocentric model of the universe, new versions of the celestial sphere model were introduced, with the planetary spheres following this sequence from the central Sun: Mercury, Venus, Earth-Moon, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn.

Mainstream belief in the theory of celestial spheres did not survive the Scientific Revolution. In the early 1600s, Kepler continued to discuss celestial spheres, although he did not consider that the planets were carried by the spheres but held that they moved in elliptical paths described by Kepler's laws of planetary motion. In the late 1600s, Greek and medieval theories concerning the motion of terrestrial and celestial objects were replaced by Newton's law of universal gravitation and Newtonian mechanics, which explain how Kepler's laws arise from the gravitational attraction between bodies.