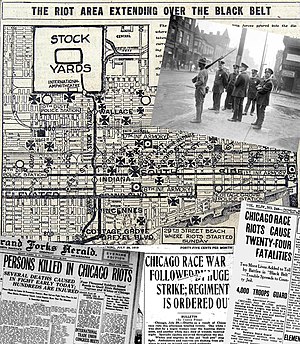

| Part of the Red Summer and the Nadir of American race relations | |

Five police officers and a National Guard soldier with a rifle and bayonet standing on a corner in the Douglas neighborhood | |

| Date | July 27 – August 3, 1919 |

|---|---|

| Location | Chicago, United States |

| Deaths | 38 |

| Part of a series on the |

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

|

The Chicago race riot of 1919 was a violent racial conflict between white Americans and black Americans that began on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois, on July 27 and ended on August 3, 1919.[1][2] During the riot, 38 people died (23 black and 15 white).[3] Over the week, injuries attributed to the episodic confrontations stood at 537, two-thirds black and one-third white; and between 1,000 and 2,000 residents, most of them black, lost their homes.[4] Due to its sustained violence and widespread economic impact, it is considered the worst of the scores of riots and civil disturbances across the United States during the "Red Summer" of 1919, so named because of its racial and labor violence.[5] It was also one of the worst riots in the history of Illinois.[6]

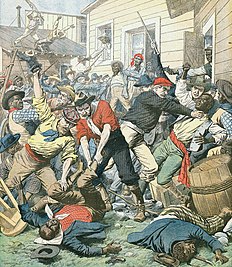

In early 1919, the sociopolitical atmosphere of Chicago around its rapidly growing black community was one of ethnic tension caused by long-standing racism, competition among new groups, an economic slump, and the social changes engendered by World War I. With the Great Migration, thousands of African Americans from the American South had settled next to neighborhoods of European immigrants on Chicago's South Side, near jobs in the stockyards, meatpacking plants, and industry. Meanwhile, the long-established Irish fiercely defended their neighborhoods and political power against all newcomers.[7][8] Post-World War I racism and social tensions built up in the competitive labor and housing markets.[9] Overcrowding and increased African-American resistance against racism, especially by war veterans, contributed to the racial tension,[5] as did white-ethnic gangs unrestrained by police.[9]

The turmoil came to a boil during a summer heat wave with the murder of the 17-year-old Eugene Williams, an African-American teenager[10] who inadvertently had drifted into a white swimming area at an informally segregated beach near 29th Street.[11][page needed] A group of African-American youths were diving from a 14-foot by 9-foot raft that they had constructed. When the raft drifted into the unofficial "white beach" area, one white beachgoer was indignant; he began hurling rocks at the young men, striking Williams, and caused the teen to drown.[12] When black beach-goers complained that whites attacked them, violence expanded into neighborhoods. Tensions between groups arose in a melee, which became days of unrest.[5] Black neighbors near white areas were attacked, white gangs went into black neighborhoods, and black workers going to and from work were attacked. Meanwhile, some black civilians organized to resist and protect each other, and some whites sought to lend aid to black civilians, but the Chicago Police Department often turned a blind eye, or worse, to the violence. Chicago Mayor William Hale Thompson had a game of brinksmanship with Illinois Governor Frank Lowden that may have exacerbated the riot, since Thompson refused to ask Lowden to send in the Illinois Army National Guard for four days, although Lowden had called up the guardsmen, organized in Chicago's armories and ready to intervene.[13]

After the riots, Lowden convened the Chicago Commission on Race Relations, a nonpartisan, interracial committee, to investigate the causes and to propose solutions to racial tensions.[4] Their conclusions were published by the University of Chicago Press as The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot.[14] U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and the U.S. Congress attempted to promote legislation and organizations to decrease racial discord in America.[5] Governor Lowden took several actions at Thompson's request to quell the riot and promote greater harmony in its aftermath.[15][16] Sections of Chicago industry were shut down for several days during and after the riots to avoid interaction among the opposing groups.[15][17] Thompson drew on his association with the riot to influence later political elections.[18] One of the most lasting effects may have been decisions in both white and black communities to seek greater racial separation.[1]

- ^ a b Lee, William (July 19, 2019). "'Ready to Explode': How a Black Boy's Drifting Raft Triggered a Deadly Week of Riots 100 Years Ago in Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Essig, Steven (2005). "Race Riots". The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

TCRRwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Editorial: Chicago's race riots of 1919 and the epilogue that resonates today". Chicago Tribune. The Editorial Board. June 19, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d "Chicago Race Riot of 1919". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- ^ "Street Battles at -Night" (PDF). The New York Times. August 3, 1919. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

ChiHIwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

HiC1919was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

CaIERwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Loerzel, Robert (August 1, 2019). "Searching for Eugene Williams". Chicago Magazine. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ Roth, Randolph (2012). American Homicide. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674064119.

- ^ Loerzel, Robert (July 23, 2019). "Blood in the Streets". Chicago Magazine. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ Krist, Gary (2012). City of Scoundrels: The Twelve Days of Disaster That Gave Birth to Modern Chicago. New York: Crown. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-307-45429-4.

- ^ "The Negro in Chicago: a study of race relations and a race riot". Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1922.

- ^ a b "Troopers Restore Order in Chicago" (PDF). The New York Times. August 2, 1919. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

SBANwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

RiCKMCwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Thompson v. McCormicks". Time. November 3, 1930. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved May 2, 2008.