| Chicano Movement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Chicanismo | |||

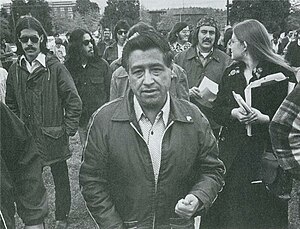

Cesar Chavez with demonstrators | |||

| Date | 1940s to 1970s | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by | Racism in the United States, Zoot Suit Riots | ||

| Goals | Civil and political rights | ||

| Methods | Boycotts, Direct action, Draft evasion, Occupations, Protests, School walkouts | ||

| Status | (continued activism by Chicano groups) | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

The Chicano Movement, also referred to as El Movimiento (Spanish for "the Movement"), was a social and political movement in the United States that worked to embrace a Chicano/a identity and worldview that combated structural racism, encouraged cultural revitalization, and achieved community empowerment by rejecting assimilation.[1][2] Chicanos also expressed solidarity and defined their culture through the development of Chicano art during El Movimiento, and stood firm in preserving their religion.[3]

The Chicano Movement was influenced by and entwined with the Black power movement, and both movements held similar objectives of community empowerment and liberation while also calling for Black–Brown unity.[4][5] Leaders such as César Chávez, Reies Tijerina, and Rodolfo Gonzales learned strategies of resistance and worked with leaders of the Black Power movement. Chicano organizations like the Brown Berets and Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) were influenced by the political agenda of Black activist organizations such as the Black Panthers. Chicano political demonstrations, such as the East L.A. walkouts and the Chicano Moratorium, occurred in collaboration with Black students and activists.[4][2]

Similar to the Black Power movement, the Chicano Movement experienced heavy state surveillance, infiltration, and repression from U.S. government informants and agent provocateurs through organized activities such as COINTELPRO. Movement leaders like Rosalio Muñoz were ousted from their positions of leadership by government agents, organizations such as MAYO and the Brown Berets were infiltrated, and political demonstrations such as the Chicano Moratorium became sites of police brutality, which led to the decline of the movement by the mid-1970s.[6][7][8][9] Other reasons for the movement's decline include its centering of the masculine subject, which marginalized and excluded Chicanas,[10][11][12] and a growing disinterest in Chicano nationalist constructs such as Aztlán.[13]

- ^ Rodriguez, Marc Simon (2014). Rethinking the Chicano Movement. Taylor & Francis. p. 64. ISBN 9781136175374.

- ^ a b Rosales, F. Arturo (1996). Chicano! The History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement. Arte Publico Press. pp. xvi. ISBN 9781611920949.

- ^ Gudis, Catherine (2013). "I Thought California Would be Different: Defining California through Visual Culture". A Companion to California History. pp. 40–74. doi:10.1002/9781444305036.ch3. ISBN 978-1-4443-0503-6.

- ^ a b Mantler, Gordon K. (2013). Power to the Poor: Black-Brown Coalition and the Fight for Economic Justice, 1960-1974. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 65–89. ISBN 9781469608068.

- ^ Martinez HoSang, Daniel (2013). "Changing Valence of White Racial Innocence". Black and Brown in Los Angeles: Beyond Conflict and Coalition. University of California Press. pp. 120–23.

- ^ Kunkin, Art (1972). "Chicano Leader Tells of Starting Violence to Justify Arrests". The Chicano Movement: A Historical Exploration of Literature. Los Angeles Free Press. pp. 108–110. ISBN 9781610697088.

- ^ Montoya, Maceo (2016). Chicano Movement for Beginners. For Beginners. pp. 192–93. ISBN 9781939994646.

- ^ Delgado, Héctor L. (2008). Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society. SAGE Publications. p. 274. ISBN 9781412926942.

- ^ Suderburg, Erika (2000). Space, Site, Intervention: Situating Installation Art. University of Minnesota Press. p. 191. ISBN 9780816631599.

- ^ Gutiérrez-Jones, Carl (1995). Rethinking the Borderlands: Between Chicano Culture and Legal Discourse. University of California Press. p. 134. ISBN 9780520085794.

- ^ Orosco, José-Antonio (2008). Cesar Chavez and the Common Sense of Nonviolence. University of New Mexico Press. pp. 71–72, 85. ISBN 9780826343758.

- ^ Saldívar-Hull, Sonia (2000). Feminism on the Border: Chicana Gender Politics and Literature. University of California Press. pp. 29–34. ISBN 9780520207332.

- ^ Rhea, Joseph Tilden (1997). Race Pride and the American Identity. Harvard University Press. pp. 77–78. ISBN 9780674005761.