Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryotic cells.[1] The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important roles in reinforcing the DNA during cell division, preventing DNA damage, and regulating gene expression and DNA replication. During mitosis and meiosis, chromatin facilitates proper segregation of the chromosomes in anaphase; the characteristic shapes of chromosomes visible during this stage are the result of DNA being coiled into highly condensed chromatin.

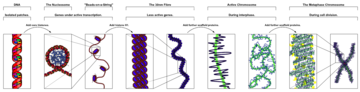

The primary protein components of chromatin are histones. An octamer of two sets of four histone cores (Histone H2A, Histone H2B, Histone H3, and Histone H4) bind to DNA and function as "anchors" around which the strands are wound.[2] In general, there are three levels of chromatin organization:

- DNA wraps around histone proteins, forming nucleosomes and the so-called beads on a string structure (euchromatin).

- Multiple histones wrap into a 30-nanometer fiber consisting of nucleosome arrays in their most compact form (heterochromatin).[a]

- Higher-level DNA supercoiling of the 30 nm fiber produces the metaphase chromosome (during mitosis and meiosis).

Many organisms, however, do not follow this organization scheme. For example, spermatozoa and avian red blood cells have more tightly packed chromatin than most eukaryotic cells, and trypanosomatid protozoa do not condense their chromatin into visible chromosomes at all. Prokaryotic cells have entirely different structures for organizing their DNA (the prokaryotic chromosome equivalent is called a genophore and is localized within the nucleoid region).

The overall structure of the chromatin network further depends on the stage of the cell cycle. During interphase, the chromatin is structurally loose to allow access to RNA and DNA polymerases that transcribe and replicate the DNA. The local structure of chromatin during interphase depends on the specific genes present in the DNA. Regions of DNA containing genes which are actively transcribed ("turned on") are less tightly compacted and closely associated with RNA polymerases in a structure known as euchromatin, while regions containing inactive genes ("turned off") are generally more condensed and associated with structural proteins in heterochromatin.[4] Epigenetic modification of the structural proteins in chromatin via methylation and acetylation also alters local chromatin structure and therefore gene expression. There is limited understanding of chromatin structure and it is active area of research in molecular biology.

- ^ Monday, Tanmoy (July 2010). "Characterization of the RNA content of chromatin". Genome Res. 20 (7): 899–907. doi:10.1101/gr.103473.109. PMC 2892091. PMID 20404130.

- ^ Maeshima, K., Ide, S., & Babokhov, M. (2019). Dynamic chromatin organization without the 30 nm fiber. Current opinion in cell biology, 58, 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2019.02.003

- ^ Hansen, Jeffrey (March 2012). "Human mitotic chromosome structure: what happened to the 30-nm fibre?". The EMBO Journal. 31 (7): 1621–1623. doi:10.1038/emboj.2012.66. PMC 3321215. PMID 22415369.

- ^ Dame, R.T. (May 2005). "The role of nucleoid-associated proteins in the organization and compaction of bacterial chromatin". Molecular Microbiology. 56 (4): 858–870. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04598.x. PMID 15853876. S2CID 26965112.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).