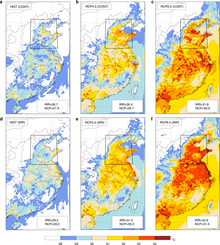

Climate change is particularly important in Asia, as the continent accounts for the majority of the human population. Warming since the 20th century is increasing the threat of heatwaves across the entire continent.[3]: 1459 Heatwaves lead to increased mortality, and the demand for air conditioning is rapidly accelerating as the result. By 2080, around 1 billion people in the cities of South and Southeast Asia are expected to experience around a month of extreme heat every year.[3]: 1460 The impacts on water cycle are more complicated: already arid regions, primarily located in West Asia and Central Asia, will see more droughts, while areas of East, Southeast and South Asia which are already wet due to the monsoons will experience more flooding.[3]: 1459

The waters around Asia are subjected to the same impacts as elsewhere, such as the increased warming and ocean acidification.[3]: 1465 There are many coral reefs in the region, and they are highly vulnerable to climate change,[3]: 1459 to the point practically all of them will be lost if the warming exceeds 1.5 °C (2.7 °F).[4][5] Asia's distinctive mangrove ecosystems are also highly vulnerable to sea level rise.[3]: 1459 Asia also has more countries with large coastal populations than any other continent, which would cause large economic impacts from sea level rise.[3]: 1459 Water supplies in the Hindu Kush region will become more unstable as its enormous glaciers, known as the "Asian water towers", gradually melt.[3]: 1459 These changes to water cycle also affect vector-borne disease distribution, with malaria and dengue fever expected to become more prominent in the tropical and subtropical regions.[3]: 1459 Food security will become more uneven, and South Asian countries could experience significant impacts from global food price volatility.[3]: 1494

Historical emissions from Asia are lower than those from Europe and North America. However, China has been the single largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the 21st century, while India is the third-largest. As a whole, Asia currently accounts for 36% of world's primary energy consumption, which is expected to increase to 48% by 2050. By 2040, it is also expected to account for 80% of the world's coal and 26% of the world's natural gas consumption.[3]: 1468 While the United States remains the world's largest oil consumer, by 2050 it is projected to move to third place, behind China and India.[3]: 1470 While nearly half of the world's new renewable energy capacity is built in Asia,[3]: 1470 this is not yet sufficient in order to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. They imply that the renewables would account for 35% of total energy consumption in Asia by 2030.[3]: 1471

Climate change adaptation is already a reality for many Asian countries, with a wide range of strategies attempted across the continent.[3]: 1534 Important examples include the growing implementation of climate-smart agriculture in certain countries or the "sponge city" planning principles in China.[3]: 1534 While some countries have drawn up extensive frameworks such as the Bangladesh Delta Plan or Japan's Climate Adaptation Act,[3]: 1508 others still rely on localized actions that are not effectively scaled up.[3]: 1534

- ^ "How melting glaciers contributed to floods in Pakistan". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 2022-09-09. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ^ "Pakistan not to blame for climate crisis-fuelled flooding, says PM Shehbaz Sharif". the Guardian. 2022-08-31. Archived from the original on 2022-09-08. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Shaw, R., Y. Luo, T. S. Cheong, S. Abdul Halim, S. Chaturvedi, M. Hashizume, G. E. Insarov, Y. Ishikawa, M. Jafari, A. Kitoh, J. Pulhin, C. Singh, K. Vasant, and Z. Zhang, 2022: Chapter 10: Asia. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability [H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, New York, US, pp. 1457–1579 |doi=10.1017/9781009325844.012.

- ^ Armstrong McKay, David; Abrams, Jesse; Winkelmann, Ricarda; Sakschewski, Boris; Loriani, Sina; Fetzer, Ingo; Cornell, Sarah; Rockström, Johan; Staal, Arie; Lenton, Timothy (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points". Science. 377 (6611): eabn7950. doi:10.1126/science.abn7950. hdl:10871/131584. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 36074831. S2CID 252161375.

- ^ Armstrong McKay, David (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points – paper explainer". climatetippingpoints.info. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Kang, Suchul; Eltahir, Elfatih A. B. (31 July 2018). "North China Plain threatened by deadly heatwaves due to climate change and irrigation". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 3528. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14.3528K. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-38906-7. PMC 10319847. PMID 37402712.