| Colfax massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Reconstruction era | |||||||

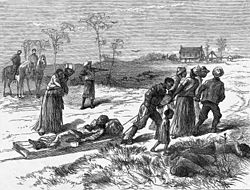

Gathering the dead after the Colfax massacre, published in Harper's Weekly, May 10, 1873 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Courthouse attackers

|

Courthouse occupiers

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3 dead | Between 62 and 153 dead | ||||||

Location within Louisiana | |||||||

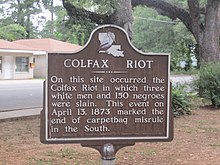

The Colfax massacre, sometimes referred to as the Colfax riot, occurred on Easter Sunday, April 13, 1873, in Colfax, Louisiana, the parish seat of Grant Parish. An estimated 62–153 Black men were murdered while surrendering to a mob of former Confederate soldiers and members of the Ku Klux Klan. Three White men also died during the confrontation.

After the contested 1872 election for governor of Louisiana and local offices, a group of White men armed with rifles and a small cannon overpowered Black freedmen and state militia occupying the Grant Parish courthouse in Colfax.[1][2] Most of the freedmen were killed after surrendering, and nearly another 50 were killed later that night after being held as prisoners for several hours. Estimates of the number of dead have varied over the years, ranging from 62 to 153; three Whites died but the number of Black victims was difficult to determine because many bodies were thrown into the Red River or removed for burial, possibly at mass graves.[3]

Historian Eric Foner described the massacre as the worst instance of racial violence during Reconstruction.[1] In Louisiana, it had the most fatalities of any of the numerous violent events occurring after the disputed gubernatorial contest in 1872 between Republicans and Democrats. Foner wrote, "...every election [in Louisiana] between 1868 and 1876 was marked by rampant violence and pervasive fraud".[4] Although the Fusionist-dominated state "returning board," which ruled on vote validity, initially declared John McEnery and his Democratic slate the winners, the board eventually divided, with a faction declaring Republican William P. Kellogg the victor. A Republican federal judge in New Orleans ruled that the Republican-majority legislature be seated.[5]

Federal prosecution and conviction of a few perpetrators at Colfax by the Enforcement Acts was appealed to the Supreme Court. In a major case, the court ruled in United States v. Cruikshank (1876) that protections of the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to persons acting individually, but only to the actions of state governments. After this ruling, the federal government could no longer use the Enforcement Act of 1870 to prosecute actions by paramilitary groups such as the White League, which had chapters forming across Louisiana beginning in 1874. Intimidation, murders, and Black voter suppression by such paramilitary groups were instrumental to the Democratic Party regaining political control of the state legislature by the late 1870s.

During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, historians have given renewed attention to the events at Colfax and the resulting Supreme Court case.[6]

- ^ a b Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, p. 437

- ^ Ulysses S. Grant, People and Events: "The Colfax Massacre", PBS Website Archived April 21, 2004, at the Wayback Machine, accessed April 6, 2008

- ^ "In a small Louisiana town, two monuments to white supremacy stand on public ground". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ Foner, Eric. (1989) Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, New York: Perennial Library p. 550

- ^ Lane 2008, p. b13

- ^ William Briggs and Jon Krakauer (August 28, 2020). "The Massacre That Emboldened White Supremacists". The New York Times.