| Territory of Colorado | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organized incorporated territory of the United States | |||||||||||||||

| 1861–1876 | |||||||||||||||

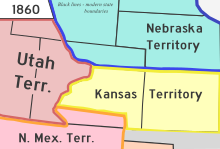

The Territory of Colorado as shown imposed on an 1860 map of the Nebraska, Kansas, New Mexico, and Utah Territories. | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Denver City 1861-1862 Colorado City 1862 Golden City 1862-1867 Denver[a] 1867-1876 | ||||||||||||||

| • Type | Organized incorporated territory | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

| 28 February 1861 | |||||||||||||||

| 1 August 1876 | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

The Territory of Colorado was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from February 28, 1861,[2] until August 1, 1876, when it was admitted to the Union as the 38th State of Colorado.[3]

The territory was organized in the wake of the Pike's Peak Gold Rush of 1858–1862, which brought the first large concentration of white settlement to the region. The organic legislative act creating the slave-free Territory of Colorado was passed by the United States Congress and signed by 15th President James Buchanan (1791-1868, served 1857-1861), into law on February 28, 1861. During that period which at the same time (since beginning with South Carolina the previous December 1860), the secession of seven, later eleven southern slave states had been occurring those several months proclaiming / forming a new independent Southern government of the Confederate States of America (which eventually grew in the next year by two more divided state governments to thirteen in the Confederacy, with two alleged western territories) that precipitated the American Civil War of April 1861 to June 1865. The boundaries of the Federals' newly designated Colorado Territory were essentially identical with those of the current / modern State of Colorado, with lands taken from the four surrounding previous Federal territories of Nebraska, Kansas, New Mexico, and Utah (Deseret) established during the 1850s. The organization of the new territory helped solidify Union / Federal control over the mineral-rich area of the western Rocky Mountains. Statehood was regarded as fairly imminent with the expected growth in the constantly westward moving population, but the local territorial ambitions for full statehood were thwarted at the end of the war in 1865 by a constitutional veto by newly sworn in 17th President Andrew Johnson (1808-1875, served 1865-1869), who was a War Democrat who succeeded to the office after briefly only serving one month as Vice President after Lincoln's assassination that April. Statehood for the territory was a recurring issue during the subsequent Ulysses S. Grant presidential administration, with Republican 18th President Grant advocating statehood against a less willing Congress during the following post-war Reconstruction era (1865-1877). After a long constant lobbying campaign, the old Colorado Territory finally ceased to exist after only 15 years when the State of Colorado was admitted to the Union as the 38th state during the American Centennial celebrationn in August 1876[3]

East and West of the Continental Divide, which split the North American continent and the Rocky Mountains, plus the new territory which included the western portion of the previous Kansas Territory, as well as some of the southwestern decade-old Nebraska Territory, and a small parcel of the northeastern corner of the New Mexico Territory. On the western side of the Divide, the territory included much of the eastern older Utah Territory, all of which besides its substantial while Mormon / L.D.S. population especially around the capital of Salt Lake City, was strongly controlled by the Ute and Shoshoni native tribes The Eastern Plains were held much more loosely by the intermixed Cheyenne and Arapaho, as well as by the Pawnee, Comanche and Kiowa. In 1861, ten days before the establishment of the Federal territory, the Arapaho and Cheyenne agreed with the United States government in the East in Washington, D.C. to give up most their areas of the Great Plains to white settlement but were allowed to live in their larger traditional areas, so long as they could tolerate homesteaders near their camps. By the end of the American Civil War in 1865, the Native American presence had been largely reduced or pacified through military action or peace treaties on the High Plains.

- ^ Bauer, William H.; Ozment, James L.; Willard, John H. (1990). Colorado Post Offices 1859-1989. Golden, Colorado: Colorado Railroad Historical Foundation. ISBN 0-918654-42-4.

- ^ a b Thirty-sixth United States Congress (February 28, 1861). "An Act To provide a temporary Government for the Territory of Colorado" (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c Ulysses S. Grant (August 1, 1876). "Proclamation 230—Admission of Colorado into the Union". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).