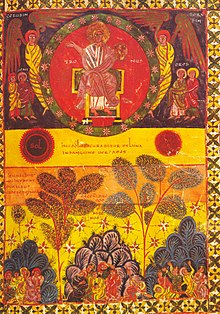

The Commentary on the Apocalypse (Commentaria in Apocalypsin) is a Latin commentary on the biblical Book of Revelation written around 776 by the Spanish monk and theologian Beatus of Liébana (c. 730–after 785).[1] The surviving texts differ somewhat, and the work is mainly famous for the spectacular illustrations in a group of illustrated manuscripts, mostly produced on the Iberian Peninsula over the following five centuries. There are 29 surviving illustrated manuscripts (many incomplete or fragments) dating from the 9th to the 13th centuries,[2] as well as other unillustrated and later manuscripts. Significant copies include the Morgan, Saint-Sever, Gerona, Osma, Madrid (Vitr 14-1), and Tábara Beatus codices.[3]

Most unusually for a theological work, the imagery seems to have been included from the start, and is considered to be the work of Beatus himself, although the earliest surviving manuscripts date from about a century after he wrote the book. After about another century, around 950, the size and number of illustrations was expanded. Manuscripts of the work are typically referred to just as a Beatus. They included a Beatus map, a version of the medieval type of world map called the T and O map with added details; this is supposed to have been created by Beatus. It has only survived in some copies.[4]

Considered together, the Beatus codices are among the most important Spanish manuscripts and have been the subject of extensive scholarly and antiquarian enquiry. The illuminated versions now represent the best known works of Mozarabic art, and had some influence on the medieval art of the rest of Europe. Among modern painters, Pablo Picasso's painting Guernica was inspired by the Saint-Sever Beatus.[5] The Morgan Beatus (in New York City's Morgan Library) inspired the artist Fernand Léger.[1], [6]

The text was not printed until 1770,[7] and later translated into Spanish for a side-by-side edition,[8] but despite modern Latin critical editions,[9] it has had little influence on biblical studies after the Middle Ages.

- ^ Williams (2017), 22

- ^ Williams (2017), 26

- ^ Williams, John (1994–2003). The Illustrated Beatus: A Corpus of the Illustrations of the Commentary on the Apocalyps, 5 vols (This is the scholarly edition, the contents of which were mined for the novel by Umberto Eco (2014). From the Tree to the Labyrinth. Harvard University Press. p. 252. ISBN 9780674728165. This counted 27 illustrated copies, but two new fragments were found subsequently, described in Williams (2017) ed.). London: Harvey Miller.

- ^ Williams (2017), 23

- ^ "The Saint-Sever Beatus". 18 January 2018.

- ^ Wasielewski, Amanda (2022). ""Interfaces of art: Meyer Schapiro, Fernand Léger and the role of the art historian in anachronistic artistic influence". Journal of Art Historiography. 26 – via ePapers repository.

- ^ In Apocalypsin. Ed. Florez, Madrid, 1770. The first known printed edition of the commentary. Latin.

- ^ Beato de Liebana: Obras Completas y Complementarias, Vol. I. BAC, 2004. The commentary translated by Alberto del Campo Hernandez and Joaquin Gonzalez Echegaray. Side by side Spanish and Latin.

- ^ Commentarius in Apocalypsin, (2 Vols.) Ed. E. Romero-Pose. Rome, 1985. The second critical edition of the commentary. Latin; Tractatus in Apocalypsin. Ed. Gryson. (Vols. 107B and 107C, Corpus Christianorum Series Latina.) Brepols, 2012. The third critical edition of the commentary. Latin, with French introductory material. Also available in a French translation by Gryson, as part of the Sources Chretiennes series, but I've never seen it myself.