This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2022) |

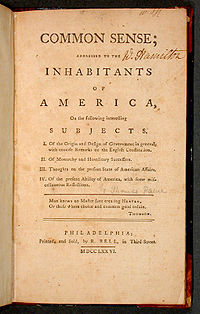

The original cover of Common Sense | |

| Author | Thomas Paine |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Published | January 10, 1776 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Pages | 47 |

| Text | Common Sense at Wikisource |

| Designations | |

|---|---|

| Official name | "Common Sense" |

| Type | City |

| Criteria |

|

| Designated | 1993 |

| Location | SE corner of S 3rd St. & Thomas Paine Place (Chancellor St), Philadelphia. Pennsylvania, U.S. 39°56′48″N 75°08′47″W / 39.9465505°N 75.1464207°W |

| Marker Text | At his print shop here, Robert Bell published the first edition of Thomas Paine's revolutionary pamphlet in January 1776. Arguing for a republican form of government under a written constitution, it played a key role in rallying American support for independence. |

Common Sense[1] is a 47-page pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–1776 advocating independence from Great Britain to people in the Thirteen Colonies. Writing in clear and persuasive prose, Paine collected various moral and political arguments to encourage common people in the Colonies to fight for egalitarian government. It was published anonymously on January 10, 1776,[2] at the beginning of the American Revolution and became an immediate sensation.

It was sold and distributed widely and read aloud at taverns and meeting places. In proportion to the population of the colonies at that time (2.5 million), it had the largest sale and circulation of any book published in American history.[3] As of 2006, it remains the all-time best-selling American title and is still in print today.[4]

Common Sense made public a persuasive and impassioned case for independence, which had not yet been given serious intellectual consideration in either Britain or the American colonies. In England, John Cartwright had published Letters on American Independence in the pages of the Public Advertiser during the early spring of 1774 advocating legislative independence for the colonies while in Virginia, Thomas Jefferson had penned A Summary View of British America three months later. Neither, however, went as far as Paine in proposing full-fledged independence.[5] Paine connected independence with common dissenting Protestant beliefs as a means to present a distinctly American political identity and structured Common Sense as if it were a sermon.[6][7] Historian Gordon S. Wood described Common Sense as "the most incendiary and popular pamphlet of the entire revolutionary era."[8]

The text was translated into French by Antoine Gilbert Griffet de Labaume in 1791.[9]

- ^ Full title: Common Sense; Addressed to the Inhabitants of America, on the Following Interesting Subjects.

- ^ Foner, Philip. "Thomas Paine". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ Conway (1893)

- ^ Kaye (2005), p. 43.

- ^ Chiu, Frances. A Routledge Guidebook to Paine's Rights of Man. Routledge, 2020. Pp. 46-56.

- ^ Wood (2002), pp. 55–56

- ^ Anthony J. Di Lorenzo, "Dissenting Protestantism as a Language of Revolution in Thomas Paine's Common Sense" (registration required) in Eighteenth-Century Thought, Vol. 4, 2009. ISSN 1545-0449.

- ^ Wood (2002), p. 55

- ^ Rosenfeld, Sophia. Common Sense: A Political History. 2011. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, page 303.