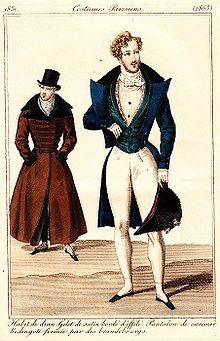

A dandy is a man who places particular importance upon physical appearance and personal grooming, refined language and leisurely hobbies. A dandy could be a self-made man both in person and persona, who emulated the aristocratic style of life regardless of his middle-class origin, birth, and background, especially during the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Britain.[1][2][3]

Early manifestations of dandyism were Le petit-maître (the Little Master) and the musk-wearing Muscadin ruffians of the middle-class Thermidorean reaction (1794–1795). Modern dandyism, however, emerged in stratified societies of Europe during the 1790s revolution periods, especially in London and Paris.[4] Within social settings, the dandy cultivated a persona characterized by extreme posed cynicism, or "intellectual dandyism" as defined by Victorian novelist George Meredith; whereas Thomas Carlyle, in his novel Sartor Resartus (1831), dismissed the dandy as "a clothes-wearing man"; Honoré de Balzac's La fille aux yeux d'or (1835) chronicled the idle life of Henri de Marsay, a model French dandy whose downfall stemmed from his obsessive Romanticism in the pursuit of love, which led him to yield to sexual passion and murderous jealousy.

In the metaphysical phase of dandyism, the poet Charles Baudelaire portrayed the dandy as an existential reproach to the conformity of contemporary middle-class men, cultivating the idea of beauty and aesthetics akin to a living religion. The dandy lifestyle, in certain respects, "comes close to spirituality and to stoicism" as an approach to living daily life,[5] while its followers "have no other status, but that of cultivating the idea of beauty in their own persons, of satisfying their passions, of feeling and thinking … [because] Dandyism is a form of Romanticism. Contrary to what many thoughtless people seem to believe, dandyism is not even an excessive delight in clothes and material elegance. For the perfect dandy, these [material] things are no more than the symbol of the aristocratic superiority of mind."[6]

The linkage of clothing and political protest was a particularly English characteristic in 18th-century Britain;[7] the sociologic connotation was that dandyism embodied a reactionary form of protest against social equality and the leveling effects of egalitarian principles. Thus, the dandy represented a nostalgic yearning for feudal values and the ideals of the perfect gentleman as well as the autonomous aristocrat – referring to men of self-made person and persona. The social existence of the dandy, paradoxically, required the gaze of spectators, an audience, and readers who consumed their "successfully marketed lives" in the public sphere. Figures such as playwright Oscar Wilde and poet Lord Byron personified the dual social roles of the dandy: the dandy-as-writer, and the dandy-as-persona; each role a source of gossip and scandal, confining each man to the realm of entertaining high society.[8]

- ^ dandy: "One who studies ostentatiously to dress fashionably and elegantly; a fop, an exquisite." (OED).

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 1989. Archived from the original on 25 June 2006. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

dude, n. U.S.A name given in ridicule to a man affecting an exaggerated fastidiousness in dress, speech, and deportment, and very particular about what is aesthetically 'good form'; hence extended to an exquisite, a dandy, 'a swell'.

- ^ Cult de soi-même, Charles Baudelaire, "Le Dandy", noted in Susann Schmid, "Byron and Wilde: The Dandy in the Public Sphere" in Julie Hibbard et al. , eds. The Importance of Reinventing Oscar: Versions of Wilde During the Last 100 Years 2002

- ^ Le Dandysme en France (1817–1839) Geneva and Paris, 1957.

- ^ Prevost 1957.

- ^ Baudelaire, Charles. "The Painter in Modern Life", essay about Constantin Guys.

- ^ Ribeiro, Aileen. "On Englishness in Dress", essay in The Englishness of English Dress. Christopher Breward, Becky Conekin, and Caroline Cox, Eds., 2002.

- ^ Schmid 2002.