| |

| Other short titles | Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 |

|---|---|

| Long title | An Act to provide for the allotment of lands in severalty to Indians on the various reservations, and to extend the protection of the laws of the United States and the Territories over the Indians, and for other purposes. |

| Nicknames | General Allotment Act of 1887 |

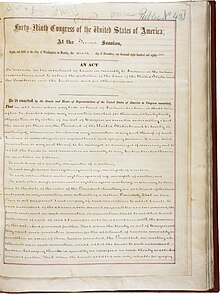

| Enacted by | the 49th United States Congress |

| Effective | February 8, 1887 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub. L. 49–105 |

| Statutes at Large | 24 Stat. 388 |

| Codification | |

| Titles amended | 25 U.S.C.: Indians |

| U.S.C. sections created | 25 U.S.C. ch. 9 § 331 et seq. |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal

28th Governor of New York

22nd & 24th President of the United States

First term

Second term

Presidential campaigns

Post-presidency

|

||

The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887[1][2]) regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the President of the United States to subdivide Native American tribal communal landholdings into allotments for Native American heads of families and individuals. This would convert traditional systems of land tenure into a government-imposed system of private property by forcing Native Americans to "assume a capitalist and proprietary relationship with property" that did not previously exist in their cultures.[3] Before private property could be dispensed, the government had to determine which Indians were eligible for allotments, which propelled an official search for a federal definition of "Indian-ness".[4]

Although the act was passed in 1887, the federal government implemented the Dawes Act on a tribe-by-tribe basis thereafter. For example, in 1895, Congress passed the Hunter Act, which administered the Dawes Act among the Southern Ute.[5] The nominal purpose of the act was to protect the property of the natives as well as to compel "their absorption into the American mainstream".[6]

Native peoples who were deemed to be mixed-blood were granted U.S. citizenship, while others were "detribalized".[4] Between 1887 and 1934, Native Americans ceded control of about 100 million acres of land (as of 2019 the United States has a total 1.9 billion acres of land[7]) or about "two-thirds of the land base they held in 1887" as a result of the act.[8] The loss of land ownership and the break-up of traditional leadership of tribes produced potentially negative cultural and social effects that have since prompted some scholars to consider the act as one of the most destructive U.S. policies for Native Americans in history.[4][3]

The "Five Civilized Tribes" (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, and Seminole) in Indian Territory were initially exempt from the Dawes Act. The Dawes Commission was established in 1893 as a delegation to register members of tribes for allotment of lands. They came to define tribal belonging in terms of blood-quantum. However, because there was no method of determining precise bloodlines, commission members often assigned "full-blood status" to Native Americans who were perceived as "poorly-assimilated" or "legally incompetent", and "mixed-blood status" to Native Americans who "most resembled whites", regardless of how they identified culturally.[4]

The Curtis Act of 1898 extended the provisions of the Dawes Act to the "Five Civilized Tribes", required the abolition of their governments and dissolution of tribal courts, allotment of communal lands to individuals registered as tribal members, and sale of lands declared surplus. This law was "an outgrowth of the land rush of 1889, and completed the extinction of Indian land claims in the territory. This violated the promise of the United States that the Indian territory would remain Indian land in perpetuity," completed the obliteration of tribal land titles in Indian Territory, and prepared for admission of the territory land to the Union as the state of Oklahoma.[9]

The Dawes Act was amended again in 1906 under the Burke Act.

During the Great Depression, the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration passed the US Indian Reorganization Act (also known as the Wheeler-Howard Law) on June 18, 1934. It prohibited any further land allotment and created a "New Deal" for Native Americans, which renewed their rights to reorganize and form self-governments in order to "rebuild an adequate land base."[10][11]

- ^ "General Allotment Act (or Dawes Act), Act of Feb. 8, 1887 (24 Stat. 388, ch. 119, 25 USCA 331), Acts of Forty-ninth Congress–Second Session, 1887". Archived from the original on May 25, 2011. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- ^ "Dawes Act (1887)". OurDocuments.gov. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b Blansett, Kent (2015). Crutchfield, James A.; Moutlon, Candy; Del Bene, Terry (eds.). The Settlement of America: An Encyclopedia of Westward Expansion from Jamestown to the Closing of the Frontier. Routledge. pp. 161–162. ISBN 9780765619846.

- ^ a b c d Grande, Sandy (2015). Red Pedagogy: Native American Social and Political Thought, 10th Anniversary Edition. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 142–143. ISBN 9781610489898.

- ^ M. B. Osburn, Katherine (1998). Mccall, Laura; Yacovone, Donald (eds.). A Shared Experience: Men, Women, and the History of Gender. NYU Press. p. 247. ISBN 9780814796832.

- ^ Friedman, Lawrence M. (2005). A History of American Law: Third Edition. Simon & Schuster. p. 387. ISBN 9780684869889.

- ^ "The U.S. Has Nearly 1.9 Billion Acres of Land. Here's How It is Used". NPR.org.

- ^ Schultz, Jeffrey D.; Aoki, Andrew L.; Haynie, Kerry L.; McCulloch, Anne M., eds. (2000). Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics: Volume 2 Hispanic Americans and Native Americans. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 608. ISBN 9781573561495.

- ^ Schultz, Jeffrey D.; Aoki, Andrew L.; Haynie, Kerry L.; McCulloch, Anne M., eds. (2000). Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics: Volume 2 Hispanic Americans and Native Americans. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 607. ISBN 9781573561495.

- ^ "The Thirties in America: Indian Reorganization Act" Archived 2013-08-28 at the Wayback Machine, Salem Press, Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ Deloria, Vine Jr. (1988). Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 54. ISBN 9780806121291.