| Ebola | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Ebola haemorrhagic fever (EHF), Ebola virus disease |

| |

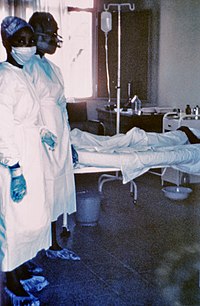

| Two nurses standing near Mayinga N'Seka, a nurse with Ebola virus disease in the 1976 outbreak in Zaire. N'Seka died a few days later. The nurses are not wearing proper protective equipment. | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, sore throat, muscular pain, headaches, diarrhoea, bleeding[1] |

| Complications | shock from fluid loss[2] |

| Usual onset | Two days to three weeks post exposure[1] |

| Causes | Ebolaviruses spread by direct contact[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Finding the virus, viral RNA, or antibodies in blood[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Malaria, cholera, typhoid fever, meningitis, other viral haemorrhagic fevers[1] |

| Prevention | Coordinated medical services, careful handling of bushmeat[1] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[1] |

| Medication | Atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab (Inmazeb) |

| Prognosis | 25–90% mortality[1] |

Ebola, also known as Ebola virus disease (EVD) and Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF), is a viral hemorrhagic fever in humans and other primates, caused by ebolaviruses.[1] Symptoms typically start anywhere between two days and three weeks after infection.[3] The first symptoms are usually fever, sore throat, muscle pain, and headaches.[1] These are usually followed by vomiting, diarrhoea, rash and decreased liver and kidney function,[1] at which point some people begin to bleed both internally and externally.[1] It kills between 25% and 90% of those infected – about 50% on average.[1] Death is often due to shock from fluid loss, and typically occurs between six and 16 days after the first symptoms appear.[2] Early treatment of symptoms increases the survival rate considerably compared to late start.[4] An Ebola vaccine was approved by the US FDA in December 2019.

The virus spreads through direct contact with body fluids, such as blood from infected humans or other animals,[1] or from contact with items that have recently been contaminated with infected body fluids.[1] There have been no documented cases, either in nature or under laboratory conditions, of spread through the air between humans or other primates.[5] After recovering from Ebola, semen or breast milk may continue to carry the virus for anywhere between several weeks to several months.[1][6][7] Fruit bats are believed to be the normal carrier in nature; they are able to spread the virus without being affected by it.[1] The symptoms of Ebola may resemble those of several other diseases, including malaria, cholera, typhoid fever, meningitis and other viral hemorrhagic fevers.[1] Diagnosis is confirmed by testing blood samples for the presence of viral RNA, viral antibodies or the virus itself.[1][8]

Control of outbreaks requires coordinated medical services and community engagement,[1] including rapid detection, contact tracing of those exposed, quick access to laboratory services, care for those infected, and proper disposal of the dead through cremation or burial.[1][9] Prevention measures involve wearing proper protective clothing and washing hands when in close proximity to patients and while handling potentially infected bushmeat, as well as thoroughly cooking bushmeat.[1] An Ebola vaccine was approved by the US FDA in December 2019.[10] While there is no approved treatment for Ebola as of 2019[update],[11] two treatments (atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab and ansuvimab) are associated with improved outcomes.[12] Supportive efforts also improve outcomes.[1] These include oral rehydration therapy (drinking slightly sweetened and salty water) or giving intravenous fluids, and treating symptoms.[1] In October 2020, atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab (Inmazeb) was approved for medical use in the United States to treat the disease caused by Zaire ebolavirus.[13]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Ebola virus disease, Fact sheet N°103, Updated September 2014". World Health Organization (WHO). September 2014. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ a b Singh SK, Ruzek D, eds. (2014). Viral hemorrhagic fevers. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 444. ISBN 978-1439884294. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016.

- ^ Modrow S, Falke D, Truyen U, Schätzl H (2013). "Viruses: Definition, Structure, Classification". In Modrow S, Falke D, Truyen U, Schätzl H (eds.). Molecular Virology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 17–30. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-20718-1_2. ISBN 978-3-642-20718-1. S2CID 83235976.

- ^ Ebola in Uganda: Guiliani R. "Our game-changing treatment centres will save more lives". msf.org.urk. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "2014 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak in West Africa". World Health Organization (WHO). 21 April 2014. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "Preliminary study finds that Ebola virus fragments can persist in the semen of some survivors for at least nine months". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 14 October 2015. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017.

- ^ "Recommendations for Breastfeeding/Infant Feeding in the Context of Ebola". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 19 September 2014. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ Broadhurst MJ, Brooks TJ, Pollock NR (13 July 2016). "Diagnosis of Ebola Virus Disease: Past, Present, and Future". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 29 (4). American Society for Microbiology: 773–793. doi:10.1128/cmr.00003-16. ISSN 0893-8512. LCCN 88647279. OCLC 38839512. PMC 5010747. PMID 27413095.

- ^ "Guidance for Safe Handling of Human Remains of Ebola Patients in U.S. Hospitals and Mortuaries". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "First FDA-approved vaccine for the prevention of Ebola virus disease, marking a critical milestone in public health preparedness and response" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 20 December 2019. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ^ "Ebola Treatment Research". NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ "Independent Monitoring Board Recommends Early Termination of Ebola Therapeutics Trial in DRC Because of Favorable Results with Two of Four Candidates". NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. 12 August 2019. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

FDA PRwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).