Education in the Thirteen Colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries varied considerably. Public school systems existed only in New England. In the 18th Century, the Puritan emphasis on literacy largely influenced the significantly higher literacy rate (70 percent of men) of the Thirteen Colonies, mainly New England, in comparison to Britain (40 percent of men) and France (29 percent of men).[1]

How much education a child received depended on a person's social and family status. Families did most of the educating, and boys were favored. Educational opportunities were much sparser in the rural South.

| This article is part of a series on |

| Education in the United States |

|---|

| Summary |

| Curriculum topics |

| Education policy issues |

| Levels of education |

|

|

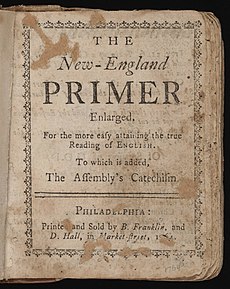

The Puritans valued education, both for the sake of religious study (they demanded a great deal of Bible reading) and for the sake of citizens who could participate better in town meetings. A 1647 Massachusetts law mandated that every town of 50 or more families support a 'petty' (elementary) school and every town of 100 or more families support a Latin, or grammar, school where a few boys could learn Latin in preparation for college and the ministry or law. In practice, virtually all New England towns made an effort to provide some schooling for their children. Both boys and girls attended the elementary schools, and there they learned to read, write, cipher, and they also learned religion. The first Catholic school for both boys and girls was established by Father Theodore Schneider in 1743 in the town of Goshenhoppen, PA (present day Bally) and is still in operation. In the mid-Atlantic region, private and sectarian schools filled the same niche as the New England common schools.[2]

The South, overwhelmingly rural, had few schools of any sort until the Revolutionary era. Wealthy children studied with private tutors; middle-class children might learn to read from literate parents or older siblings; many poor and middle-class white children, as well as virtually all black children, went unschooled. Literacy rates were significantly lower in the South than the north; this remained true until the late nineteenth century.[3] Secondary schools were rare in the colonial era outside a handful of major towns. They generally emphasized Latin grammar, rhetoric, and advanced arithmetic with the goal of preparing boys to enter college.