There are numerous interlinked effects of climate change on livestock rearing. This activity is both heavily affected by and a substantial driver of anthropogenic climate change due to its greenhouse gas emissions. As of 2011, some 400 million people relied on livestock in some way to secure their livelihood.[3]: 746 The commercial value of this sector is estimated as close to $1 trillion.[4] As an outright end to human consumption of meat and/or animal products is not currently considered a realistic goal,[5] any comprehensive adaptation to effects of climate change must also consider livestock.

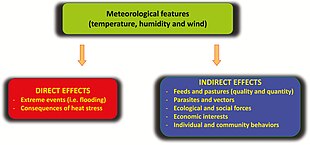

The observed adverse impacts on livestock production include increased heat stress in all but the coldest nations.[6][7] This causes both mass animal mortality during heatwaves, and the sublethal impacts, such as lower quantity of quality of products like milk, greater vulnerability to conditions like lameness or even impaired reproduction.[3] Another impact concerns reduced quantity or quality of animal feed, whether due to drought or as a secondary impact of CO2 fertilization effect. Difficulties with growing feed could reduce worldwide livestock headcounts by 7–10% by midcentury.[3]: 748 Animal parasites and vector-borne diseases are also spreading further than they had before, and the data indicating this is frequently of superior quality to one used to estimate impacts on the spread of human pathogens.[3]

While some areas which currently support livestock animals are expected to avoid "extreme heat stress" even with high warming at the end of the century, others may stop being suitable as early as midcentury.[3]: 750 In general, sub-Saharan Africa is considered to be the most vulnerable region to food security shocks caused by the impacts of climate change on their livestock, as over 180 million people across those nations are expected to see significant declines in suitability of their rangelands around midcentury.[3]: 748 On the other hand, Japan, the United States and nations in Europe are considered the least vulnerable. This is as much a product of pre-existing differences in human development index and other measures of national resilience and widely varying importance of pastoralism to the national diet as it is an outcome of direct impacts of climate on each country.[1]

Proposed adaptations to climate change in livestock production include improved cooling at animal shelters and changes to animal feed, though they are often costly or have only limited effects.[8] At the same time, livestock produces the majority of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture and demands around 30% of agricultural fresh water needs, while only supplying 18% of the global calorie intake. Animal-derived food plays a larger role in meeting human protein needs, yet is still a minority of supply at 39%, with crops providing the rest.[3]: 746–747 Consequently, plans for limiting global warming to lower levels like 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) or 2 °C (3.6 °F) assume animal-derived food will play a lower role in the global diets relative to now.[9] As such, net zero transition plans now involve limits on total livestock headcounts (including reductions of already disproportionately large stocks in countries like Ireland),[10] and there have been calls for phasing out subsidies currently offered to livestock farmers in many places worldwide.[11]

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Godber2014was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lacetera2018was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f g Kerr R.B., Hasegawa T., Lasco R., Bhatt I., Deryng D., Farrell A., Gurney-Smith H., Ju H., Lluch-Cota S., Meza F., Nelson G., Neufeldt H., Thornton P., 2022: Chapter 5: Food, Fibre and Other Ecosystem Products. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke,V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, US, pp. 1457–1579 |doi=10.1017/9781009325844.012

- ^ "FAOStat". Archived from the original on 2016-10-20. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Rasmussen, Laura Vang; Hall, Charlotte; Vansant, Emilie C.; Braber, Bowie den; Olesen, Rasmus Skov (17 September 2021). "Rethinking the approach of a global shift toward plant-based diets". One Earth. 4 (9): 1201–1204. Bibcode:2021OEart...4.1201R. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2021.08.018. S2CID 239376124.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Zhang2023was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Liu2024was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Schauberger2019was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Roth, Sabrina K.; Hader, John D.; Domercq, Prado; Sobek, Anna; MacLeod, Matthew (22 May 2023). "Scenario-based modelling of changes in chemical intake fraction in Sweden and the Baltic Sea under global change". Science of the Total Environment. 888: 2329–2340. Bibcode:2023ScTEn.88864247R. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164247. PMID 37196966. S2CID 258751271.

- ^ Lisa O'Carroll (3 November 2021). "Ireland would need to cull up to 1.3 million cattle to reach climate targets". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ "just-transition-meat-sector" (PDF).