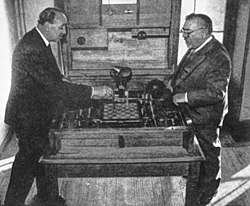

El Ajedrecista ([el axeðɾeˈθista], English: The Chess Player) is an automaton built in 1912 by Leonardo Torres Quevedo in Madrid,[2] a pioneering autonomous machine capable of playing chess.[3] As opposed to the human-operated The Turk and Ajeeb, El Ajedrecista had a true integrated automation built to play chess without human guidance. It played an endgame with three chess pieces, automatically moving a white king and a rook to checkmate the black king moved by a human opponent.

The device could be considered the first computer game in history.[4] It created great excitement when it made its debut, at the University of Paris in 1914. It was first widely mentioned in Scientific American as "Torres and His Remarkable Automatic Devices" on November 6, 1915.[5] In 1951, El Ajedrecista defeated Savielly Tartakower at the Paris Cybernetic Conference, being the first Grandmaster to lose against a machine.[6]

The automaton does not deliver checkmate in the minimum number of moves, nor always within the 50 moves allotted by the fifty-move rule, because of the simple algorithm that calculates the moves. It did, however, checkmate the opponent every time.[7] If an illegal move was made by the opposite player, the automaton would signal it by turning on a light. If the opposing player made three illegal moves, the automaton would stop playing.[8]

- ^ Gizycki, Jerzy. A History of Chess. London: Abbey Library, 1972. Print.

- ^ Velasco, Juan Jesus (2014). "Leonardo Torres Quevedo, referente para la ingeniería y desconocido para el gran público".

- ^ Williams, Andrew (2017-03-16). History of Digital Games: Developments in Art, Design and Interaction. CRC Press. ISBN 9781317503811.

- ^ Montfort, Nick (2003). Twisty Little Passages: An Approach to Interactive Fiction. MIT Press. p. 76. ISBN 0-262-63318-3.

In 1912 Leonardo Torres Quevedo ... devised the first computer game ... The machine played a KRK chess endgame, playing rook and king against a person playing a lone king.

- ^ Torres and his remarkable automatic devices. Issue 2079 of Scientific American, 1915

- ^ Hooper & Whyld 1992 page 22. The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.). England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

- ^ Atkinson, George W. (1998). Chess and machine intuition. Intellect Books, pp. 21-22. ISBN 1-871516-44-7

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page).