The Eliot School rebellion was a 19th-century incident that played a significant role in the debate over what kind of Christian instruction would be available in American public schools and sparked the establishment of Catholic parochial schools nationwide.

The incident began on a Monday morning, March 7, 1859. Massachusetts law required that the Ten Commandments be recited in every classroom every morning. Bible passages were also required to be read aloud. On March 7, a teacher at the Eliot School in Boston, Miss Sophia Shepard, called on ten-year-old Thomas J. Whall to recite the Ten Commandments. Whall refused because he was Catholic and Shepard insisted that the Commandments be recited as written in the Protestant King James Bible.[1]

The following Sunday at St. Mary's Parish Sunday School, Whall was among the several hundred boys who heard Father Bernardine Wiget, a Swiss-born Jesuit[2] and an enthusiastic ultramontane, urge them not to recite Protestant prayers lest they fall into "infidelity and heresy." The parishioners passed a resolution recommending that the children be taught not to be ashamed of their religion.[1] Wiget also said he would "read out" from the pulpit the names of any boys who did recite the Protestant prayers at the Eliot School.

On Monday, March 14 Shepard again called upon Whall and he again refused. The assistant principal, McLaurin F. Cook,[3] was called. Saying "Here's a boy that refuses to repeat the Ten Commandments, and I will whip him till he yields if that takes the whole forenoon," he beat Whall's hand with a rattan stick for 30 minutes until it was cut and bleeding. The principal then told all boys who intended to refuse to recite the King James version of the commandments to leave the school. 100 boys left that day, followed by another 300 the next. Some boys reported to school with copies of the Vulgate Commandments that they were willing to recite, but they were refused admittance.[1]

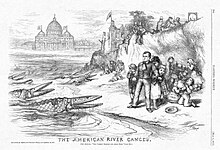

The incident attracted intense national interest.[1][4] Charges of assault and battery brought against Cook by the boy's father were dismissed on the grounds that religious instruction was a proper function of public school teachers.[3]

According to historian John McGreevy of the University of Notre Dame, the incident sparked the creation of Catholic parochial schools both in Boston and nationwide.[1][5] In Boston, St Mary's Parish created a primary school to educate the boys who had withdrawn from the Eliot School. First called St. Mary's Institute, and later named in honor of Father Wiget, the school enrolled 1,150 boys in the 1859-60 school year.[1]

- ^ a b c d e f McGreevy, John T., Catholicism and American Freedom: A History, W. W. Norton & Company, 2004 ISBN 9780393340921

- ^ Father Bernardine Wiget had fled Switzerland in 1847 during the Swiss civil war

- ^ a b Ryan, Dennis P. (1979). Beyond the ballot box: a social history of the Boston Irish, 1845-1917. ScholarWorks, University of Massachusetts-Amherst. p. 59.

- ^ "The Eliot School Difficulty at Boston Ended," March 23, 1859, New York Times.

- ^ History of the Catholic Church in the New England States, William Byrne, vol. 1, Hurd & Everts co., 1899, p. 128.