| Emphysema | |

|---|---|

| |

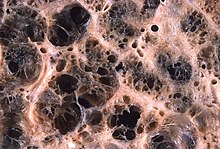

| Advanced centrilobular emphysema showing total lobule involvement on the left side | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

| Symptoms | Shortness of breath, chronic cough[1] |

| Usual onset | Over 40 years old[1] |

| Duration | Long term[1] |

| Causes | Tobacco smoking, air pollution, genetics[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Spirometry[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Asthma, congestive heart failure, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, obliterative bronchiolitis, diffuse panbronchiolitis[3] |

| Prevention | Smoking cessation, improving indoor and outdoor air quality, tobacco control measures[4] |

| Treatment | Pulmonary rehabilitation, long-term oxygen therapy, lung volume reduction[4] |

| Medication | Inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids[4] |

Emphysema is any air-filled enlargement in the body's tissues.[5] Most commonly emphysema refers to the permanent enlargement of air spaces (alveoli) in the lungs,[5][6] and is also known as pulmonary emphysema.

Emphysema is a lower respiratory tract disease,[7] characterised by enlarged air-filled spaces in the lungs, that can vary in size and may be very large. The spaces are caused by the breakdown of the walls of the alveoli, which replace the spongy lung tissue. This reduces the total alveolar surface available for gas exchange leading to a reduction in oxygen supply for the blood.[8] Emphysema usually affects the middle aged or older population because it takes time to develop with the effects of tobacco smoking, and other risk factors. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is a genetic risk factor that may lead to the condition presenting earlier.[9]

When associated with significant airflow limitation, emphysema is a major subtype of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a progressive lung disease characterized by long-term breathing problems and poor airflow.[10][11] Without COPD, the finding of emphysema on a CT lung scan still confers a higher mortality risk in tobacco smokers.[12] In 2016 in the United States there were 6,977 deaths from emphysema – 2.2 per 100,000 people.[13] Globally it accounts for 5% of all deaths.[14] A 2018 review of work on the effects of tobacco and cannabis smoking found that a possibly cumulative toxic effect could be a risk factor for developing emphysema, and spontaneous pneumothorax.[15][16]

There are four types of emphysema, three of which are related to the anatomy of the lobules of the lung – centrilobular or centriacinar, panlobular or panacinar, and paraseptal or distal acinar emphysema – and are not associated with fibrosis (scarring).[17] The fourth type is known as paracicatricial emphysema or irregular emphysema that involves the acinus irregularly and is associated with fibrosis.[17] Though the different types can be seen on imaging they are not well-defined clinically.[18] There are also a number of associated conditions, including bullous emphysema, focal emphysema, and Ritalin lung. Only the first two types of emphysema – centrilobular and panlobular – are associated with significant airflow obstruction, with that of centrilobular emphysema around 20 times more common than panlobular. Centrilobular emphysema is the only type associated with smoking.[17]

Osteoporosis is often a comorbidity of emphysema. The use of systemic corticosteroids for treating exacerbations is a significant risk factor for osteoporosis, and their repeated use is recommended against.[19]

- ^ a b c d "Emphysema". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- ^ Gold Report 2021, pp. 20–23, Chapter 2: Diagnosis and initial assessment.

- ^ Gold Report 2021, pp. 33–35, Chapter 2: Diagnosis and initial assessment.

- ^ a b c Gold Report 2021, pp. 40–46, Chapter 3: Evidence supporting prevention and maintenance therapy.

- ^ a b "Definition of Emphysema". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ Lumb AB (2017). "Airways Disease". Nunn's Applied Respiratory Physiology. Elsevier. p. 389–405.e2. doi:10.1016/b978-0-7020-6294-0.00027-7. ISBN 978-0-7020-6294-0.

Emphysema is defined as permanent enlargement of airspaces distal to the terminal bronchiole accompanied by destruction of alveolar walls.

- ^ "ICD-11 – ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ Saladin K (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 650. ISBN 9780071222075.

- ^ Murphy A, Danaher L. "Pulmonary emphysema". radiopaedia.org. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Algusti AG, et al. (2017). "Definition and Overview". Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). pp. 6–17.

- ^ Roversi S, Corbetta L, Clini E (5 May 2017). "GOLD 2017 recommendations for COPD patients: toward a more personalized approach" (PDF). COPD Research and Practice. 3. doi:10.1186/s40749-017-0024-y.

- ^ Diedtra Henderson (2014-12-16). "Emphysema on CT Without COPD Predicts Higher Mortality Risk". Medscape.

- ^ "FastStats – Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease". www.cdc.gov. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ Martini K, Frauenfelder T (November 2020). "Advances in imaging for lung emphysema". Annals of Translational Medicine. 8 (21): 1467. doi:10.21037/atm.2020.04.44. PMC 7723580. PMID 33313212.

- ^ Underner M, Urban T, Perriot J, et al. (December 2018). "REVUE GÉNÉRALE – Pneumothorax spontané et emphysème pulmonaire chez les consommateurs de cannabis" [Spontaneous pneumothorax and lung emphysema in cannabis users]. Revue de pneumologie clinique (in French). 74 (6): 400–415. doi:10.1016/j.pneumo.2018.06.003. PMID 30420278. S2CID 59233744.

- ^ Coffey D (15 November 2022). "Buzz Kill: Lung Damage Looks Worse in Pot Smokers". Medscape.

- ^ a b c Kumar 2018, pp. 498–501.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Smithwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "COPD and comorbidities" (PDF). p. 133. Retrieved 24 September 2019.