This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 21,000 words. (June 2024) |

Enoch Powell | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

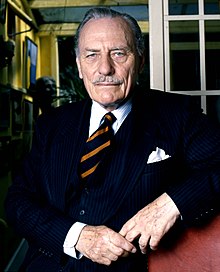

1987 portrait | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Shadow Secretary of State for Defence | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 7 July 1965 – 21 April 1968 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader | Edward Heath | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Peter Thorneycroft | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Reginald Maudling | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Minister of Health | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 27 July 1960 – 18 October 1963 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Harold Macmillan | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Derek Walker-Smith | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Anthony Barber | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Financial Secretary to the Treasury | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 14 January 1957 – 15 January 1958 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Harold Macmillan | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Henry Brooke | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Jack Simon | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | John Enoch Powell 16 June 1912 Birmingham, England | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 8 February 1998 (aged 85) London, England | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Warwick Cemetery, Warwick, England | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Pamela Wilson (m. 1952) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | British Army | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1939–1945 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Brigadier | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Unit | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Awards | Member of the Order of the British Empire (1943) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism |

|---|

|

John Enoch Powell MBE (16 June 1912 – 8 February 1998) was a British politician, scholar, and writer. He served as Member of Parliament (MP) for Wolverhampton South West for the Conservative Party from 1950 to February 1974 and as MP for South Down for the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) from October 1974 to 1987. He was Minister of Health from 1960 to 1963 in the second Macmillan ministry and was Shadow Secretary of State for Defence from 1965 to 1968 in the Shadow Cabinet of Ted Heath. Before entering politics he was a classical scholar. He served in both staff and intelligence positions during the Second World War, reaching the rank of brigadier. Powell also wrote poetry, and several books on classical and political subjects.

In 1968, while serving as Shadow Defence Secretary, Powell attracted attention nationwide for his "Rivers of Blood" speech, in which he criticised immigration to the UK, especially rapid immigration from the New Commonwealth, and opposed the anti-discrimination Race Relations Bill (which ultimately became law). The speech was criticised by some of Powell's own party members[1] and The Times.[2] Heath, who was then the leader of the Conservative Party and the leader of the Opposition, dismissed Powell from the Shadow Cabinet the day after the speech.

In the aftermath of the speech several polls suggested that 67 to 82 per cent of the British population agreed with Powell's opinions.[3][4][5] His supporters argued that Powell's large public following[6][7] helped the Conservatives to win the 1970 general election,[8] and perhaps cost them the February 1974 general election,[9] when Powell turned his back on the Conservatives by endorsing a vote for the Labour Party, which returned as a minority government. Powell was returned to the House of Commons in October 1974 as the Ulster Unionist Party MP for the Northern Ireland constituency of South Down. He represented the constituency until he was defeated at the 1987 general election.

- ^ Heffer 1998, p. 461

- ^ Editorial comment, The Times, 22 April 1968.

- ^ Shepherd 1994, p. 352.

- ^ Schwarz, Bill (2011), The White Man's World, OUP Oxford, p. 48, ISBN 9780199296910,

So far as these can tell us anything, the opinion polls following the speech provide an indication of the scale of popular support. Gallup recorded 74 per cent, ORC 82 per cent, NOP 67 per cent, and the Express 79 per cent in favour of what Powell had proposed in Birmingham.

- ^ Garvey, Bruce (4 June 2008). "Part 2: Enoch Powell and the 'Rivers of Blood' speech". The Ottawa Citizen. Canada.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ Dumbrell, John (2001), A Special Relationship, Macmillan, pp. 34–35, ISBN 9780333622490,

A Feb 1969 Gallup poll showed Powell the 'most admired person' in British public opinion

- ^ OnTarget, vol. 8, ALOR, archived from the original on 19 February 2011, retrieved 2 January 2011

- ^ Heffer 1998, p. 568.

- ^ Heffer 1998, pp. 710–712.