This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2021) |

| Fallopian tube | |

|---|---|

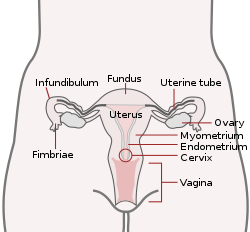

Uterus and fallopian tubes labelled as uterine tubes | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Paramesonephric ducts |

| System | Reproductive system |

| Artery | Tubal branches of ovarian artery, tubal branch of uterine artery via mesosalpinx |

| Lymph | Lumbar lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tuba uterina |

| Greek | σάλπιγξ (sálpinx) |

| MeSH | D005187 |

| TA98 | A09.1.02.001 |

| TA2 | 3486 |

| FMA | 18245 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The fallopian tubes, also known as uterine tubes, oviducts[1] or salpinges (sg.: salpinx), are paired tubular sex organs in the human female body that stretch from the ovaries to the uterus. The fallopian tubes are part of the female reproductive system. In other vertebrates, they are only called oviducts.[2]

Each tube is a muscular hollow organ[3] that is on average between 10 and 14 cm (3.9 and 5.5 in) in length, with an external diameter of 1 cm (0.39 in).[4] It has four described parts: the intramural part, isthmus, ampulla, and infundibulum with associated fimbriae. Each tube has two openings: a proximal opening nearest to the uterus, and a distal opening nearest to the ovary. The fallopian tubes are held in place by the mesosalpinx, a part of the broad ligament mesentery that wraps around the tubes. Another part of the broad ligament, the mesovarium suspends the ovaries in place.[5]

An egg cell is transported from an ovary to a fallopian tube where it may be fertilized in the ampulla of the tube. The fallopian tubes are lined with simple columnar epithelium with hairlike extensions called cilia, which together with peristaltic contractions from the muscular layer, move the fertilized egg (zygote) along the tube. On its journey to the uterus, the zygote undergoes cell divisions that changes it to a blastocyst, an early embryo, in readiness for implantation.[6]

Almost a third of cases of infertility are caused by fallopian tube pathologies. These include inflammation, and tubal obstructions. A number of tubal pathologies cause damage to the cilia of the tube, which can impede movement of the sperm or egg.[7]

The name comes from the Italian Catholic priest and anatomist Gabriele Falloppio, for whom other anatomical structures are also named.[8]

- ^ "Uterine Tube (Fallopian Tube) Anatomy: Overview, Pathophysiological Variants". 14 July 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Zhao, W; Zhu, Q; Yan, M; Li, C; Yuan, J; Qin, G; Zhang, J (February 2015). "Levonorgestrel decreases cilia beat frequency of human fallopian tubes and rat oviducts without changing morphological structure". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 42 (2): 171–8. doi:10.1111/1440-1681.12337. PMC 6680194. PMID 25399777.

- ^ Han, Joan; Sadiq, Nazia M. (2022). "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Fallopian Tube". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31613440. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ "Fallopian Tube Disorders: Overview, Salpingitis and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease, Salpingitis Isthmica Nodosa". 15 March 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ Craig, Morgan E.; Sudanagunta, Sneha; Billow, Megan (2022). "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Broad Ligaments". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29763118. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ Tortora, Gerard J. (2010). Principles of anatomy and physiology (12th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 1103. ISBN 9780470233474.

- ^ Briceag I, Costache A, Purcarea VL, Cergan R, Dumitru M, Briceag I, Sajin M, Ispas AT (2015). "Fallopian tubes--literature review of anatomy and etiology in female infertility". J Med Life. 8 (2): 129–31. PMC 4392087. PMID 25866566.

- ^ Castro PT, Aranda OL, Marchiori E, de Araújo LF, Alves HD, Lopes RT, Werner H, Araujo Júnior E (2020). "Proportional vascularization along the fallopian tubes and ovarian fimbria: assessment by confocal microtomography". Radiol Bras. 53 (3): 161–166. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2019.0080. PMC 7302899. PMID 32587423.