| Father Le Loutre's War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

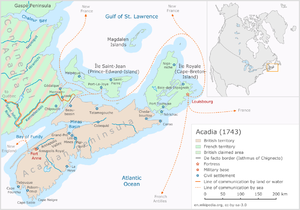

Map of Acadia, c. 1743. The conflict was primarily fought in Acadia. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia.c On one side of the conflict, the British and New England colonists were led by British officer Charles Lawrence and New England Ranger John Gorham. On the other side, Father Jean-Louis Le Loutre led the Mi'kmaq and the Acadia militia in guerrilla warfare against settlers and British forces.[9]: 148 At the outbreak of the war there were an estimated 2500 Mi'kmaq and 12,000 Acadians in the region.[10]: 127

While the British captured Port Royal in 1710 and were ceded peninsular Acadia in 1713, the Mi'kmaq and Acadians continued to contain the British in settlements at Port Royal and Canso. The rest of the colony was in the control of the Catholic Mi'kmaq and Acadians. About forty years later, the British made a concerted effort to settle Protestants in the region and to establish military control over all of Nova Scotia and present-day New Brunswick, igniting armed response from Acadians in Father Le Loutre's War. The British settled 3,229 people in Halifax during the first years. This exceeded the number of Mi'kmaq in the entire region and was seen as a threat to the traditional occupiers of the land.d The Mi'kmaq and some Acadians resisted the arrival of these Protestant settlers.

The war caused unprecedented upheaval in the area. Atlantic Canada witnessed more population movements, more fortification construction, and more troop allocations than ever before.[11] Twenty-four conflicts were recorded during the war (battles, raids, skirmishes), thirteen of which were Mi'kmaq and Acadian raids on the capital region Halifax/Dartmouth. As typical of frontier warfare, many additional conflicts were unrecorded.

During Father Le Loutre's War, the British attempted to establish firm control of the major Acadian settlements in peninsular Nova Scotia and to extend their control to the disputed territory of present-day New Brunswick. The British also wanted to establish Protestant communities in Nova Scotia. During the war, the Acadians and Mi'kmaq left Nova Scotia for the French colonies of Ile St. Jean (Prince Edward Island) and Ile Royale (Cape Breton Island). The French also tried to maintain control of the disputed territory of present-day New Brunswick. (Father Le Loutre tried to prevent the New Englanders from moving into present-day New Brunswick just as a generation earlier, during Father Rale's War, Rale had tried to prevent New Englanders from taking over present-day Maine.) Throughout the war, the Mi'kmaq and Acadians attacked the British forts in Nova Scotia and the newly established Protestant settlements. They wanted to retard British settlement and buy time for France to implement its Acadian resettlement scheme.[9]: 154–155 [12]: 47

The war began with the British establishing Halifax, settling more British settlers within six months than there were Mi'kmaq. In response, the Acadians and Mi'kmaq orchestrated attacks at Chignecto, Grand Pré, Dartmouth, Canso, Halifax and Country Harbour. The French erected forts at present-day Fort Menagoueche, Fort Beauséjour and Fort Gaspareaux. The British responded by attacking the Mi'kmaq and Acadians at Mirligueche (later known as Lunenburg), Chignecto and St. Croix. The British unilaterally established communities in Lunenburg and Lawrencetown. Finally, the British erected forts in Acadian communities located at Windsor, Grand Pré and Chignecto. The war ended after six years with the defeat of the Mi'kmaq, Acadians and French in the Battle of Fort Beauséjour.

- ^ Johnson, Micheline D. (1979). "Germain, Charles". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Johnson, Micheline D. (1974). "Daudin, Henri". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Johnson, Micheline D. (1979). "Girard, Jacques". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Johnson, Micheline D. (1974). "Manach, Jean". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Sutherland, Maxwell (1979). "Brewse, John". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ "Tracking Jeremiah Rogers, Privateer, to Oak Island". The Oak Island Compendium. November 27, 2017. Archived from the original on January 16, 2020.

- ^ George E. E. Nichols (March 15, 1904). Notes on Nova Scotian Privateers (Report). Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society.

- ^ Burke, Edmund (1786). "The Annual Register, Or, A View of the History, Politics, and Literature for the Year".

- ^ a b Grenier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3876-3.

- ^ Patterson, Stephen E. (1994). "1744–1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples". In Phillip Buckner; John G. Reid (eds.). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. pp. 125–155. ISBN 978-1-4875-1676-5. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt15jjfrm.

- ^ Johnson, John (2005). "French attitudes toward the Acadians". In Ronnie Gilles LeBlanc (ed.). Du Grand Dérangement à la Déportation: nouvelles perspectives historiques. Université de Moncton. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-897214-02-2.

- ^ Patterson, Stephen E. (Autumn 1993). "Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749–61: A Study in Political Interaction". Acadiensis. 23 (1): 23–59. JSTOR 30303469.