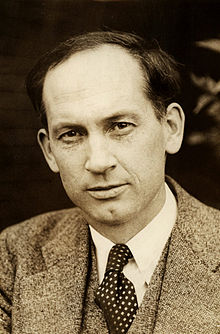

Harold Innis | |

|---|---|

Innis in the 1920s | |

| Born | November 5, 1894 Otterville, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | November 8, 1952 (aged 58) Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | |

| Doctoral advisor | Chester W. Wright[1] |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | |

| Sub-discipline | |

| School or tradition | Toronto School |

| Institutions | University of Toronto |

| Doctoral students | S. D. Clark[2] |

| Notable students | Albert Faucher[3] |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable ideas | |

| Influenced | |

Harold Adams Innis FRSC (November 5, 1894 – November 8, 1952) was a Canadian professor of political economy at the University of Toronto and the author of seminal works on media, communication theory, and Canadian economic history. He helped develop the staples thesis, which holds that Canada's culture, political history, and economy have been decisively influenced by the exploitation and export of a series of "staples" such as fur, fish, lumber, wheat, mined metals, and coal. The staple thesis dominated economic history in Canada from the 1930s to 1960s, and continues to be a fundamental part of the Canadian political economic tradition.[7] Innis has been referred to as the "father of communications theory"[8] and as the "father of Canadian economic history".[9]

Innis's writings on communication explore the role of media in shaping the culture and development of civilizations.[10] He argued, for example, that a balance between oral and written forms of communication contributed to the flourishing of Greek civilization in the 5th century BC.[11] He warned, however, that Western civilization is now imperiled by powerful, advertising-driven media obsessed by "present-mindedness" and the "continuous, systematic, ruthless destruction of elements of permanence essential to cultural activity."[12] His intellectual bond with Eric A. Havelock formed the foundations of the Toronto School of communication theory, which provided a source of inspiration for future members of the school Marshall McLuhan and Edmund Snow Carpenter.[13]

Innis laid the basis for scholarship that looked at the social sciences from a distinctly Canadian point of view. As the head of the University of Toronto's political economy department, he worked to build up a cadre of Canadian scholars so that universities would not continue to rely as heavily on British or American-trained professors unfamiliar with Canada's history and culture. He was successful in establishing sources of financing for Canadian scholarly research.[14]

As the Cold War grew hotter after 1947, Innis grew increasingly hostile to the United States. He warned repeatedly that Canada was becoming a subservient colony to its much more powerful southern neighbor. "We are indeed fighting for our lives", he warned, pointing especially to the "pernicious influence of American advertising.... We can only survive by taking persistent action at strategic points against American imperialism in all its attractive guises."[15] His views influenced some younger scholars, including Donald Creighton.[16]

Innis also tried to defend universities from political and economic pressures. He believed that independent universities, as centres of critical thought, were essential to the survival of Western civilization.[17] His intellectual disciple and university colleague, Marshall McLuhan, lamented Innis's premature death as a disastrous loss for human understanding. McLuhan wrote: "I am pleased to think of my own book The Gutenberg Galaxy as a footnote to the observations of Innis on the subject of the psychic and social consequences, first of writing then of printing."[18] Mel Watkins declared that Innis was "without doubt the most distinguished social scientist and historian, and one of the most distinguished intellectuals, that Canada has ever produced".[19]

- ^ Heyer, p. 30.

- ^ Buxton, William J. (2004). "The 'Values' Discussion Group at the University of Toronto, February–May 1949". Canadian Journal of Communication. 29 (2): 200. doi:10.22230/cjc.2004v29n2a1435. ISSN 1499-6642.

- ^ Buxton, William J. (2013). "Introduction: North by Northwest; Harold Innis and 'the Advancement of Knowledge of the Canadian North'". In Buxton, William J. (ed.). Harold Innis and the North: Appraisals and Contestations. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-7735-8876-9.

- ^ Angus, Ian (2017). "Extended Body ... Extended Mind: The Risk of Thought". Invited Lecture Presented at the Conference: Affect, Activism, and New Media: Theoretical Provocations. Tanner Humanities Center, University of Utah, 5–7 October 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ Henderson, Stuart Robert (2007). Making the Scene: Yorkville and Hip Toronto, 1960–1970 (PhD thesis). Kingston, Ontario: Queen's University. p. 119. hdl:1974/820.

- ^ Stanford, Jim (2013). "Re: 'The Past Reframes Itself,' by Mel Watkins". Literary Review of Canada. Toronto. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ Easterbrook, W.T. and Watkins, M.H. (1984) "The Staple Approach." In Approaches to Canadian Economic History. Ottawa: Carleton Library Series, Carleton University Press, pp. 1–98.

- ^ Williams, David (2003). Imagined Nations: Reflections on Media in Canadian Fiction. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-7735-2516-0.

- ^ Duan, Peng; Zhang, Lei; Song, Kai; Han, Xiao (2020). Communication of Smart Media. Singapore: Springer Singapore. p. 14. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-9464-9. ISBN 978-981-15-9463-2.

- ^ Babe, Robert E. (2000) "The Communication Thought of Harold Adams Innis." In Canadian Communication Thought: Ten Foundational Writers. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 51–88.

- ^ Heyer, Paul. (2003) Harold Innis. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc., p. 66.

- ^ Innis, Harold. (1952) Changing Concepts of Time. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, p. 15.

- ^ "Harold Adams Innis". Library Archives Canada. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ Watson, Alexander John. (2006) Marginal Man: The Dark Vision of Harold Innis. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 14–23.

- ^ Harold A. Innis (2004). Changing Concepts of Time. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 13–14. ISBN 9780742528185.

- ^ Donald Wright (2015). Donald Creighton: A Life in History. University of Toronto Press. pp. 174–75. ISBN 9781442620308.

- ^ Innis, Harold. (1951) "A Plea for Time." In The Bias of Communication. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 83–89.

- ^ McLuhan, Marshall. (2005) Marshall McLuhan Unbound. Corte Madera, CA : Gingko Press v. 8, p. 8. This is a reprint of McLuhan's introduction to the 1964 edition of Innis's book The Bias of Communication first published in 1951.

- ^ Babe, Robert E. (2015). Wilbur Schramm and Noam Chomsky Meet Harold Innis: Media, Power, and Democracy. Critical media studies. Lanham: Lexington Books. pp. xiii. ISBN 978-0-7391-2368-3.