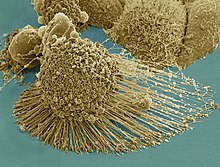

HeLa (/ˈhiːlɑː/) is an immortalized cell line used in scientific research. It is the oldest human cell line and one of the most commonly used.[1][2] HeLa cells are durable and prolific, allowing for extensive applications in scientific study.[3][4] The line is derived from cervical cancer cells taken on February 8, 1951,[5] from Henrietta Lacks, a 31-year-old African American mother of five, after whom the line is named. Lacks died of cancer on October 4, 1951.[6]

The cells from Lacks's cancerous cervical tumor were taken without her knowledge, which was common practice in the United States at the time.[7] Cell biologist George Otto Gey found that they could be kept alive,[8] and developed a cell line. Previously, cells cultured from other human cells would survive for only a few days, but cells from Lacks's tumor behaved differently.

- ^ Rahbari R, Sheahan T, Modes V, Collier P, Macfarlane C, Badge RM (2009). "A novel L1 retrotransposon marker for HeLa cell line identification". BioTechniques. 46 (4): 277–284. doi:10.2144/000113089. PMC 2696096. PMID 19450234.

- ^ Morris, Rhys Bowen (August 2, 2023). "What were the top 100 cell lines of 2022?". CiteAb Blog. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ Capes-Davis A, Theodosopoulos G, Atkin I, Drexler HG, Kohara A, MacLeod RA, Masters JR, Nakamura Y, Reid YA, Reddel RR, Freshney RI (2010). "Check your cultures! A list of cross-contaminated or misidentified cell lines". Int. J. Cancer. 127 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1002/ijc.25242. PMID 20143388. S2CID 2929020.

- ^ Batts DW (May 10, 2010). "Cancer cells killed Henrietta Lacks – then made her immortal". The Virginian-Pilot. pp. 1, 12–14. Archived from the original on November 25, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Scherer, W.F.; Syverton, J.T.; Gey, G.O. (1953). "Studies on the propagation in vitro of poliomyelitis viruses. IV. Viral multiplication in a stable strain of human malignant epithelial cells (strain HeLa) derived from an epidermoid carcinoma of the cervix". Journal of Experimental Medicine. 97 (5): 695–710. doi:10.1084/jem.97.5.695. PMC 2136303. PMID 13052828.

- ^ "Johns Hopkins Magazine -- April 2000". pages.jh.edu.

- ^ Ron Claiborne; Sydney Wright, IV (January 31, 2010). "How One Woman's Cells Changed Medicine". ABC World News. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ^ McKie, Robin (April 3, 2010). "Henrietta Lacks's cells were priceless, but her family can't afford a hospital". The Guardian. London. Retrieved July 18, 2017.