Henry Clifford | |

|---|---|

| 10th Baron Clifford | |

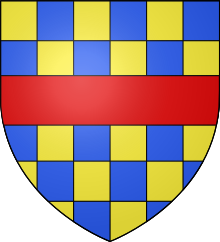

Arms of Clifford, Chequy or and azure a fess gules | |

| Predecessor | John Clifford, 9th Baron Clifford |

| Successor | Henry Clifford, 1st Earl of Cumberland |

| Born | c. 1454 |

| Died | 23 April 1523 |

Henry Clifford, 10th Baron Clifford KB (c. 1454 – 23 April 1523)[1] was an English nobleman. His father, John Clifford, 9th Baron Clifford, was killed in the Wars of the Roses fighting for the House of Lancaster when Henry was around five years old. A local legend later developed that—on account of John Clifford having killed one of the House of York's royal princes in battle, and the new Yorkist King Edward IV seeking revenge—Henry was spirited away by his mother. As a result, it was said, he grew up ill-educated, living a pastoral life in the care of a shepherd family. Thus, ran the story, Clifford was known as the "shepherd lord". More recently, historians have questioned this narrative, noting that for a supposedly ill-educated man, he was signing charters only a few years after his father's death, and that in any case, Clifford was officially pardoned by King Edward in 1472. It may be that he deliberately avoided attracting Yorkist attention in his early years, although probably not to the extent portrayed in the local mythology.

The Yorkist regime came to an end in 1485 with the invasion of Henry Tudor, who defeated Edward's brother, Richard III, at the Battle of Bosworth Field. Henry's victory meant that he needed men to control the North of England for him, and Clifford's career as a loyal Tudor servant began. Soon after Bosworth, the King gave him responsibility for crushing the last remnants of rebellion in the north. Clifford was not always successful in this, and his actions were not always popular. On more than one occasion, he found himself at loggerheads with the city of York, the civic leadership of which was particularly independently minded. When another Yorkist rebellion broke out in 1487, Clifford suffered an embarrassing military defeat by the rebels outside the city walls. Generally, however, royal service was extremely profitable for him: King Henry needed trustworthy men in the region and was willing to build up their authority in order to protect his own.

Although Clifford's later years were devoted to service in the north and fighting the Scots (he took part in the decisive English victory at Flodden in 1513) he fell out with the King on numerous occasions. Clifford was not an easy-going personality; his abrasiveness caused trouble with his neighbours, occasionally breaking out in violent feuds. This was not the behaviour the King expected from his lords. Furthermore, Clifford had married a cousin of the King, yet Clifford's infidelity to her was notorious among his contemporaries. This also drew the King's ire, to the extent that the couple's separation was mooted. Clifford's first wife had died by 1511, and Clifford remarried. This was also a tempestuous match, and on one occasion he and his wife ended up in court accusing each other of adultery. Clifford's relations with his eldest son and heir, the eventual Henry Clifford, 1st Earl of Cumberland, were equally turbulent. Clifford rarely attended the royal court himself, but sent his son to be raised with the King's heir, Prince Arthur. Clifford later complained that young Henry not only lived above his station, he consorted with men of bad influence; Clifford also accused his son of regularly beating up his father's servants on his return to Yorkshire.

Clifford outlived the King and attended the coronation of Henry VIII in 1509. While continuing to serve as the King's man in the north, Clifford carried on his feuds with the local gentry. He also indulged his interests in astronomy, for which he built a small castle for observation purposes. Clifford grew ill in 1522 and died in April of the following year; his widow later remarried. Young Henry inherited the title as 11th Baron Clifford as well as a large fortune and estate, the result of his father's policy of frugality and avoiding the royal court for most of his life.