| Hepatic encephalopathy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Portosystemic encephalopathy, hepatic coma,[1] coma hepaticum |

| |

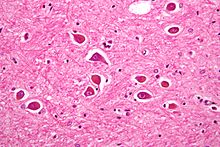

| Micrograph of Alzheimer type II astrocytes, as may be seen in hepatic encephalopathy | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Altered level of consciousness, mood changes, personality changes, movement problems[2] slurred speech, Sleep problems, Anxiety or irritability, Muscle twitches (myoclonus), Difficulty concentrating or short attention span, Flapping hand motion (asterixis), Reduced alertness, Cognitive impairment (confused thinking or judgment).[3] |

| Complications | hepatic coma.[3] |

| Types | Acute, recurrent, persistent[4] |

| Causes | Liver failure[2] |

| Risk factors | Infections, GI bleeding, constipation, electrolyte problems, certain medications[5] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after ruling out other possible causes[2][6] |

| Differential diagnosis | Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome, delirium tremens, hypoglycemia, subdural hematoma, hyponatremia[1] |

| Treatment | Supportive care, treating triggers, lactulose, liver transplant[1][4] |

| Prognosis | Average life expectancy less than a year in those with severe disease[1] |

| Frequency | Affects >40% with cirrhosis[7] |

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is an altered level of consciousness as a result of liver failure.[2] Its onset may be gradual or sudden.[2] Other symptoms may include movement problems, changes in mood, or changes in personality.[2] In the advanced stages it can result in a coma.[4]

Hepatic encephalopathy can occur in those with acute or chronic liver disease.[4] Episodes can be triggered by infections, GI bleeding, constipation, electrolyte problems, or certain medications.[5] The underlying mechanism is believed to involve the buildup of ammonia in the blood, a substance that is normally removed by the liver.[2] The diagnosis is typically based on symptoms after ruling out other potential causes.[2][6] It may be supported by blood ammonia levels, an electroencephalogram, or a CT scan of the brain.[4][6]

Hepatic encephalopathy is possibly reversible with treatment.[1] This typically involves supportive care and addressing the triggers of the event.[4] Lactulose is frequently used to decrease ammonia levels.[1] Certain antibiotics (such as rifaximin) and probiotics are other potential options.[1] A liver transplant may improve outcomes in those with severe disease.[1]

More than 40% of people with cirrhosis develop hepatic encephalopathy.[7] More than half of those with cirrhosis and significant HE live less than a year.[1] In those who are able to get a liver transplant, the risk of death is less than 30% over the subsequent five years.[1] The condition has been described since at least 1860.[1]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Wijdicks, EF (27 October 2016). "Hepatic Encephalopathy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 375 (17): 1660–1670. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1600561. PMID 27783916.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Hepatic encephalopathy". GARD. 2016. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Hepatic encephalopathy". Clevelandclinic. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Cash WJ, McConville P, McDermott E, McCormick PA, Callender ME, McDougall NI (January 2010). "Current concepts in the assessment and treatment of hepatic encephalopathy". QJM. 103 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcp152. PMID 19903725.

- ^ a b Starr, SP; Raines, D (15 December 2011). "Cirrhosis: diagnosis, management, and prevention". American Family Physician. 84 (12): 1353–9. PMID 22230269.

- ^ a b c "Portosystemic Encephalopathy - Hepatic and Biliary Disorders". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ a b Ferri, Fred F. (2017). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 577. ISBN 9780323529570. Archived from the original on 2017-07-30.