The history of malaria extends from its prehistoric origin as a zoonotic disease in the primates of Africa through to the 21st century. A widespread and potentially lethal human infectious disease, at its peak malaria infested every continent except Antarctica.[1] Its prevention and treatment have been targeted in science and medicine for hundreds of years. Since the discovery of the Plasmodium parasites which cause it, research attention has focused on their biology as well as that of the mosquitoes which transmit the parasites.

References to its unique, periodic fevers are found throughout recorded history, beginning in the first millennium BC in Greece and China.[2][3]

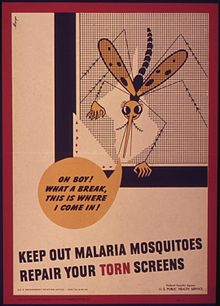

For thousands of years, traditional herbal remedies have been used to treat malaria.[4] The first effective treatment for malaria came from the bark of the cinchona tree, which contains quinine. After the link to mosquitos and their parasites was identified in the early twentieth century, mosquito control measures such as widespread use of the insecticide DDT, swamp drainage, covering or oiling the surface of open water sources, indoor residual spraying, and use of insecticide treated nets was initiated. Prophylactic quinine was prescribed in malaria endemic areas, and new therapeutic drugs, including chloroquine and artemisinins, were used to resist the scourge. Today, artemisinin is present in every remedy applied in the treatment of malaria. After introducing artemisinin as a cure administered together with other remedies, malaria mortality in Africa decreased by half, though it later partially rebounded.[5]

Malaria researchers have won multiple Nobel Prizes for their achievements, although the disease continues to afflict some 200 million patients each year, killing more than 600,000.

Malaria was the most important health hazard encountered by U.S. troops in the South Pacific during World War II, where about 500,000 men were infected.[6]

At the close of the 20th century, malaria remained endemic in more than 100 countries throughout the tropical and subtropical zones, including large areas of Central and South America, Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Africa, the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and Oceania. Resistance of Plasmodium to anti-malaria drugs, as well as resistance of mosquitos to insecticides and the discovery of zoonotic species of the parasite have complicated control measures.

One estimate, which has been published in a 2002 Nature article, claims that malaria may have killed 50-60 billion people throughout history, or about half of all humans that have ever lived.[7] However, speaking on the BBC podcast More or Less, Emeritus Professor of Medical Statistics at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine Brian Faragher voiced doubt about this estimate, noting that the Nature article in question did not reference the claim.[8][9] Faragher gave a tentative estimate of about 4-5% of deaths being caused by malaria, lower than the claimed 50%.[8] More or Less were unable to find any source for the original figure aside from works which made the claim without reference.[9]

- ^ Carter R, Mendis KN (2002). "Evolutionary and historical aspects of the burden of malaria" (PDF). Clin Microbiol Rev. 15 (4): 564–94. doi:10.1128/cmr.15.4.564-594.2002. PMC 126857. PMID 12364370. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ Neghina R, Neghina AM, Marincu I, Iacobiciu I (2010). "Malaria, a Journey in Time: In Search of the Lost Myths and Forgotten Stories". Am J Med Sci. 340 (6): 492–98. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181e7fe6c. PMID 20601857. S2CID 205747078.

- ^ The Su Wen of the Huangdi Neijing (Inner Classic of the Yellow Emperor)

- ^ Willcox ML, Bodeker G (2004). "Traditional herbal medicines for malaria" (PDF). BMJ. 329 (7475): 1156–59. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1156. PMC 527695. PMID 15539672. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ Prokurat S (2015), Economic outcomes of Malaria in South East Asia (PDF), Józefów: Opportunities for cooperation between Europe and Asia, pp. 157–74, ISBN 978-83-62753-58-1, archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2016, retrieved 5 August 2016

- ^ Bray RS (2004). Armies of Pestilence: The Effects of Pandemics on History. James Clarke. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-227-17240-7.

- ^ Whitfield, J. (2002). "Portrait of a serial killer". Nature. doi:10.1038/news021001-6.

- ^ a b Pomeroy R (3 October 2019). "Has Malaria Really Killed Half of Everyone Who Ever Lived?". RealClear Science. Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ a b Tim Harford (5 October 2013). "Have Mosquitoes Killed Half the World?". More or Less (Podcast). BBC. Retrieved 28 June 2023.