| |

Participating members (partners not shown) | |

| Formation | 24 October 2007 |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Saint-Paul-lès-Durance, France |

Membership |

|

Director-General | Pietro Barabaschi |

| Website | www |

Small-scale model of ITER | |

| Device type | Tokamak |

|---|---|

| Location | Saint-Paul-lès-Durance, France |

| Technical specifications | |

| Major radius | 6.2 m (20 ft) |

| Plasma volume | 840 m3 |

| Magnetic field | 11.8 T (peak toroidal field on coil) 5.3 T (toroidal field on axis) 6 T (peak poloidal field on coil) |

| Heating power | 320 MW (electrical input) 50 MW (thermal absorbed) |

| Fusion power | 0 MW (electrical generation) 500 MW (thermal from fusion) |

| Discharge duration | up to 1000 s |

| History | |

| Date(s) of construction | 2013–2034 |

ITER (initially the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, iter meaning "the way" or "the path" in Latin[2][3][4]) is an international nuclear fusion research and engineering megaproject aimed at creating energy through a fusion process similar to that of the Sun. It is being built next to the Cadarache facility in southern France.[5][6] Upon completion of construction of the main reactor and first plasma, planned for 2033–2034,[7][8] ITER will be the largest of more than 100 fusion reactors built since the 1950s, with six times the plasma volume of JT-60SA in Japan, the largest tokamak operating today.[9][10][11]

The long-term goal of fusion research is to generate electricity. ITER's stated purpose is scientific research, and technological demonstration of a large fusion reactor, without electricity generation.[12][9] ITER's goals are to achieve enough fusion to produce 10 times as much thermal output power as thermal power absorbed by the plasma for short time periods; to demonstrate and test technologies that would be needed to operate a fusion power plant including cryogenics, heating, control and diagnostics systems, and remote maintenance; to achieve and learn from a burning plasma; to test tritium breeding; and to demonstrate the safety of a fusion plant.[10][6]

ITER's thermonuclear fusion reactor will use over 300 MW of electrical power to cause the plasma to absorb 50 MW of thermal power, creating 500 MW of heat from fusion for periods of 400 to 600 seconds.[13] This would mean a ten-fold gain of plasma heating power (Q), as measured by heating input to thermal output, or Q ≥ 10.[14] As of 2022[update], the record for energy production using nuclear fusion is held by the National Ignition Facility reactor, which achieved a Q of 1.5 in December 2022.[15] Beyond just heating the plasma, the total electricity consumed by the reactor and facilities will range from 110 MW up to 620 MW peak for 30-second periods during plasma operation.[16] As a research reactor, the heat energy generated will not be converted to electricity, but simply vented.[6][17][18]

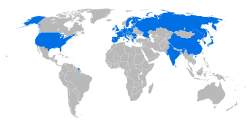

ITER is funded and run by seven member parties: China, the European Union, India, Japan, Russia, South Korea and the United States. In the immediate aftermath of Brexit, the United Kingdom continued to participate in ITER through the EU's Fusion for Energy (F4E) program;[19] however, in September 2023, the UK decided to discontinue its participation in ITER via F4E,[20] and by March 2024 had rejected an invitation to join ITER directly, deciding instead to pursue its own independent fusion research program.[21] Switzerland participated through Euratom and F4E, but the EU effectively suspended Switzerland's participation in response to the May 2021 collapse in talks on an EU-Swiss framework agreement;[22] as of 2024[update], Switzerland is considered a non-participant pending resolution of its dispute with the EU.[23] The project also has cooperation agreements with Australia, Canada, Kazakhstan and Thailand.[24]

Construction of the ITER complex in France started in 2013,[25] and assembly of the tokamak began in 2020.[26] The initial budget was close to €6 billion, but the total price of construction and operations is projected to be from €18 to €22 billion;[27][28] other estimates place the total cost between $45 billion and $65 billion, though these figures are disputed by ITER.[29][30] Regardless of the final cost, ITER has already been described as the most expensive science experiment of all time,[31] the most complicated engineering project in human history,[32] and one of the most ambitious human collaborations since the development of the International Space Station (€100 billion or $150 billion budget) and the Large Hadron Collider (€7.5 billion budget).[note 1][33][34]

ITER's planned successor, the EUROfusion-led DEMO, is expected to be one of the first fusion reactors to produce electricity in an experimental environment.[35]

- ^ "What is ITER?". ITER. 11 January 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ ITER Technical Basis. Vienna: International Atomic Energy Agency. 2002. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ "ITER, a reactor in France, may deliver fusion energy power as early as 2045". The Economist. London, England. 4 May 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

Iter (originally, "International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor", but now rebranded as Latin, thus meaning "journey", "path" or "method") will be a giant fusion reactor of a type called a tokamak.

- ^ "What is Iter". Fusion for Energy. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ The ITER project. EFDA, European Fusion Development Agreement (2006).

- ^ a b c Claessens, Michel (2020). ITER: The Giant Fusion Reactor: Bringing a Sun to Earth. Copernicus. ISBN 978-3-030-27580-8.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

ITER-2024was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Banks, Michael (3 July 2024). "ITER fusion reactor hit by massive decade-long delay and €5bn price hike". Physics World. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ a b Meade, Dale (2010). "50 years of fusion research". Nuclear Fusion. 50 (1): 014004. Bibcode:2010NucFu..50a4004M. doi:10.1088/0029-5515/50/1/014004. ISSN 0029-5515. S2CID 17802364.

- ^ a b "What Will ITER Do?". ITER. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ "Main Research Objectives – JT-60SA". Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ Tirone, Jonathan (29 October 2019). "Chasing Unlimited Energy With the World's Largest Fusion Reaction". Bloomberg Businessweek. New York, USA: Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Overton, Thomas (1 June 2020). "Fusion Energy Is Coming, and Maybe Sooner Than You Think". Power. Rockville, MD, USA: Power Group. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ "Facts & Figures". ITER. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ "DOE National Laboratory Makes History by Achieving Fusion Ignition". 13 December 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ^ "Power Supply". ITER. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ "Will ITER make more energy than it consumes?". www.jt60sa.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ Fountain, Henry (27 March 2017). "A Dream of Clean Energy at a Very High Price". The New York Times. New York, USA. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Coblentz, Laban (11 January 2021). "Brexit | The UK will remain part of ITER". ITER. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Matthews, David (11 September 2023). "UK mulls associate membership of ITER fusion project after ditching full participation". Science|Business. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Sparkes, Matthew (1 March 2024). "UK spurns European invitation to join ITER nuclear fusion project". New Scientist. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Bradley, Simon (2 May 2022). "EU-Swiss political deadlock throws shadow over nuclear fusion research". SWI swissinfo.ch. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "ITER Members". ITER. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "ITER Members". ITER. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ "ITER Tokamak complex construction begins". Nuclear Engineering International. 24 June 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Paul Rincon (28 July 2020). "Iter: World's largest nuclear fusion project begins assembly". BBC. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ De Clercq, Geert (7 October 2016). "Nuclear fusion reactor ITER's construction accelerates as cost estimate swells". London, England: Reuters. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Hutt, Rosamond (14 May 2019). "Scientists just got closer to making nuclear fusion work". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Claessens, Michel (29 May 2020). "Breakthrough at the ITER Fusion Reactor Paves Way for Energy Source That May Alter the Course of Civilization". New York, USA: Newsweek. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Kramer, David (16 April 2018). "ITER disputes DOE's cost estimate of fusion project". Physics Today. No. 4. College Park, MD, USA: American Institute of Physics. doi:10.1063/PT.6.2.20180416a. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Clery, Daniel (27 June 2013). "Inside the Most Expensive Science Experiment Ever". Popular Science. Winter Park, FL, USA: Bonnier Corporation. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Cohen, Ariel (7 August 2020). "ITER, The World's Largest Nuclear Fusion Project: A Big Step Forward". Forbes. New York, USA: Integrated Whale Media. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Parisi, Jason; Ball, Justin (2019). The Future of Fusion Energy. Singapore: World Scientific. doi:10.1142/9781786345431_0007. ISBN 978-1-78634-542-4. S2CID 239317702.

- ^ "France gets nuclear fusion plant". BBC. 28 June 2005. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ "The demonstration power plant: DEMO". EUROfusion. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).