Ibn al-Jawzi | |

|---|---|

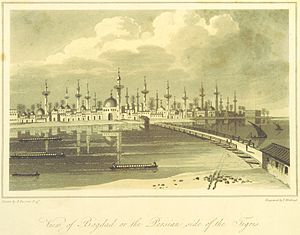

A depiction of Baghdad from 1808, taken from the print collection in Travels in Asia and Africa, etc. (ed. J. P. Berjew, British Library); Ibn al-Jawzī spent his entire life in this city in the twelfth-century. | |

| Jurisconsult, Preacher, Traditionist; Shaykh of Islam, Orator of Kings and Princes, Imam of the Hanbalites | |

| Venerated in | Sunni Islam, but particularly in the Hanbali school of jurisprudence |

| Major shrine | Green Cement Tomb at Baghdad, Iraq |

Ibn al-Jawzi | |

|---|---|

| Title | Shaykh al-Islam[1] |

| Personal | |

| Born | c. 510 AH/1116 CE |

| Died | 12 Ramadan 597 AH/16 June 1201 (aged approximately 84) |

| Religion | Islam |

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

| Denomination | Sunni |

| Jurisprudence | Hanbali |

| Creed | Ash'ari[2][3][4] |

| Main interest(s) | History, Tafsir, Hadith, Fiqh |

| Notable work(s) | Daf' Shubah al-Tashbih |

| Muslim leader | |

Influenced | |

Abū al-Farash ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿAlī ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Jawzī,[8] often referred to as Ibn al-Jawzī (Arabic: ابن الجوزي; c. 1116 – 16 June 1201) for short, was a Muslim jurisconsult, preacher, orator, heresiographer, traditionist, historian, judge, hagiographer, and philologist[8] who played an instrumental role in propagating the Hanbali school of orthodox Sunni jurisprudence in his native Baghdad during the twelfth-century.[8] During "a life of great intellectual, religious and political activity,"[8] Ibn al-Jawzi came to be widely admired by his fellow Hanbalis for the tireless role he played in ensuring that that particular school – historically, the smallest of the four principal Sunni schools of law – enjoy the same level of "prestige" often bestowed by rulers on the Maliki, Shafi'i, and Hanafi rites.[8]

Ibn al-Jawzi received a "very thorough education"[8] during his adolescent years, and was fortunate to train under some of that era's most renowned Baghdadi scholars, including Ibn al-Zāg̲h̲ūnī (d. 1133), Abū Bakr al-Dīnawarī (d. 1137–8), Sayyid Razzāq Alī Jīlānī (d. 1208), and Abū Manṣūr al-Jawālīkī (d. 1144–5).[9] Although Ibn al-Jawzi's scholarly career continued to blossom over the next few years, he became most famous during the reign of al-Mustadi (d. 1180), the thirty-third Abbasid caliph, whose support for Hanbalism allowed Ibn al-Jawzi to effectively become "one of the most influential persons" in Baghdad, due to the caliph's approval of Ibn al-Jawzi's public sermonizing to huge crowds in both pastoral and urban areas throughout Baghdad.[10] In the vast majority of the public sermons delivered during al-Mustadi's reign, Ibn al-Jawzi often presented a stanch defense of the prophet Muhammad's example, and vigorously criticized all those whom he considered to be schismatics in the faith.[10] At the same time, Ibn al-Jawzi's reputation as a scholar continued to grow due to the substantial role he played in managing many of the most important universities in the area,[10] as well as on account of the sheer number of works he wrote during this period.[10] As regards the latter point, it is important to note that part of Ibn al-Jawzi's legacy rests on his reputation for having been "one of the most prolific writers" of all time.[8] As scholars have noted, Ibn al-Jawzi's prodigious corpus, "varying in length" as it does,[8] touches upon virtually "all the great disciplines" of classical Islamic study.[8]

- ^ Al-Dhahabi, Siyar A'lam al-Nubala'.

- ^ J. A. Boyle (1968). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 5 of The Saljuq and Mongol Periods. Cambridge University Press. p. 299. ISBN 9780521069366.

Talbis Iblis, by the Ash'ari theologian Ibn al-Jawzi, contains strong attacks on the Sufis, though the author makes a distinction between an older purer Sufism and the "modern" one,

- ^ Gibril Fouad Haddad (2015). The Biographies of the Elite Lives of the Scholars, Imams & Hadith Masters. As-Sunnah Foundation of America. p. 226.

Abu al-Faraj bin al-Jawzi al-Qurashi al-Taymi al-Bakri al-Baghdadi al-Hanbali al-Ashari (509/510-597AH).

- ^ Ibn al-Ahdal (1964). Ahmad Bakīr Mahmud (ed.). Kashf al-Ghata' 'an Haqa'iq al-Tawhid كشف الغطاء عن حقائق التوحيد (PDF) (in Arabic). Tunisia: Tunisian General Labour Union. p. 83.

وكل هؤلاء الذين ذكرنا عقائدهم من أئمة الشافعية سوى القرشي والشاذلي فمالكيان أشعريان. ولنتبع ذلك بعقيدة المالكية وعقيدتين للحنفية ليعلم أن غالب أهل هذين المذهبين على مذهب الأشعري في العقائد، وبعض الحنبلية في الفروع يكونون على مذهب الأشعري في العقائد كالشيخ عبد القادر الجيلاني وابن الجوزي وغيرهما رضي الله عنهم. وقد تقدم وسيأتي أيضاً أن الأشعري والإمام أحمد كانا في الاعتقاد متفقين حتى حدث الخلاف من أتباعه القائلين بالحرف والصوت والجهة وغير ذلك فلهذا لم نذكر عقائد المخالفين واقتصرنا على عقائد أصحابنا الأشعرية ومن وافقهم من المالكية والحنفية رضي الله عنهم. فأما عقيدة المالكية فهي تأليف الشيخ الإمام الكبير الشهير أبي محمد عبد الله بن أبي زيد المالكي ذكرها في صدر كتابه الرسالة

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

sahwahwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Robinson:2003:XV

- ^ "Ibn Al-Jawzi". Sunnah.org. Archived from the original on 2020-02-22. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cite error: The named reference

Laoust - Ibn al-D̲j̲awzīwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Ibn Rajab, Dhayl ʿalā Ṭabaqāt al-ḥanābila, Cairo 1372/1953, i, 401

- ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

Ibn Rajab 404-405was invoked but never defined (see the help page).