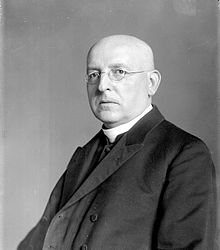

Ignaz Seipel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chancellor of Austria | |

| In office 20 October 1926 – 4 May 1929 | |

| President | Michael Hainisch Wilhelm Miklas |

| Vice-Chancellor | Franz Dinghofer Karl Hartleb |

| Preceded by | Rudolf Ramek |

| Succeeded by | Ernst Streeruwitz |

| In office 31 May 1922 – 20 November 1924 | |

| President | Michael Hainisch |

| Vice-Chancellor | Felix Frank |

| Preceded by | Johannes Schober |

| Succeeded by | Rudolf Ramek |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 30 September 1930 – 4 December 1930 | |

| Preceded by | Johannes Schober |

| Succeeded by | Johannes Schober |

| In office 20 October 1926 – 4 May 1929 | |

| Preceded by | Rudolf Ramek |

| Succeeded by | Ernst Streeruwitz |

| Minister of Social Welfare | |

| In office 27 October 1918 – 11 November 1918 | |

| Prime Minister | Heinrich Lammasch |

| Preceded by | Viktor Mataja |

| Succeeded by | Ferdinand Hanusch |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 19 July 1876 Vienna, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 2 August 1932 (aged 56) Pernitz, Austria |

| Resting place | Vienna Central Cemetery |

| Political party | Christian Social Party |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

Ignaz Seipel (19 July 1876 – 2 August 1932) was an Austrian Catholic priest and conservative politician, who served as the Chancellor of the First Austrian Republic twice during the 1920s and leader of the Christian Social Party. He is considered the most prominent statesman of the Austrian right in the interwar period.

Born into a modest bourgeois family, Seipel grew up in the town of Meidling, near Vienna, where he completed his studies before enrolling at the University of Vienna. He studied theology and was ordained as a priest in 1899. After serving in a rural parish, he returned to the imperial capital to pursue a doctorate. In 1908, he became an assistant professor of moral theology at the University of Vienna, and a year later, a full professor of the same discipline at the University of Salzburg, where he taught for the next eight years.

Seipel took an interest in social, educational, and economic issues and became friends with Heinrich Lammasch, a prominent Austrian jurist and the last Imperial Minister-President, who appointed him Minister of Social Welfare in his cabinet in late 1918. Although a monarchist, Seipel played a key role in helping the Christian Socialists accept the new republican system. He built up political Catholicism by aligning the clericals with Vienna's large bourgeoisie, often of Jewish descent. Over time, his political stance evolved: while initially a strong supporter of the Austria–Hungary and the Habsburg dynasty, after World War I, he adopted a conciliatory approach toward socialists and democracy to prevent the establishment of a left-wing dictatorship. Later, between 1922 and 1924, he distanced himself from the socialists, forming alliances with capitalist and anti-Marxist groups. Disillusioned with democracy, by 1927, Seipel advocated for replacing it with an authoritarian system with clerical.

A dominant figure in Austrian politics during the 1920s, Seipel served as Chancellor from 31 May 1922 to 3 April 1929, except for a period between 1924 and 1926. In 1922, he managed to end severe inflation through an international stabilization loan, although this meant subjecting state economic policy to the supervision of the League of Nations. Deeply anti-socialist, he led a government coalition of Christian Socialists and Pan-Germans. Considered brilliant and the most capable conservative politician of his time, Seipel shared with his socialist rival, Otto Bauer, a firm commitment to defending their principles. Within his party, Seipel belonged to the most radical and conservative faction, which included the most capable leaders. Even when not leading the government, he wielded significant influence in the Christian Social Party. He played a crucial role in both the Christian Socialists' acceptance of the republic and their eventual abandonment of democracy. In his later years, Seipel supported constitutional reforms to establish an authoritarian government and worked closely with fascist groups like the Heimwehr (Home Guard), an organization similar to the German Freikorps. He died in 1932, suffering from diabetes and tuberculosis.