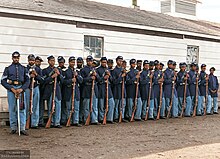

The infantry in the American Civil War comprised foot-soldiers who fought primarily with small arms and carried the brunt of the fighting on battlefields across the United States. The vast majority of soldiers on both sides of the Civil War fought as infantry and were overwhelmingly volunteers who joined and fought for a variety of reasons. Early in the war, there was great variety in how infantry units were organized and equipped - many copied famous European formations such as the Zouaves - but as time progressed there was more uniformity in their arms and their equipment.

Historians have debated whether the evolution of infantry tactics between 1861 and 1865 marked a seminal point in the evolution of warfare. The conventional narrative is that officers adhered stubbornly to the tactics of the Napoleonic Wars, in which armies employed linear formations and favored open fields over the usage of cover. However, the greater accuracy and range of the rifle musket rendered these tactics obsolete. The result was greater casualties and increasing usage of trench warfare, presaging the course of future conflicts. More recent scholarship has challenged this viewpoint and argued the impact of the rifled musket was minimal. In this interpretation, the tactics used remained practical and the decisiveness of battles was affected by other factors.

This debate has implications not only for the nature of the soldier's experience, but also for the broader question of the Civil War's relative modernity. Williamson Murray and Wayne Wei-Siang Hsieh argue that the conflict was resulted from "the combination...of the Industrial Revolution and French Revolution [which] allowed the opposing sides to mobilize immense numbers of soldiers while projecting military power over great distances."[1]

- ^ Murray, Williamson; Hsieh, Wayne Wei-lara (2016). A Savage War: A Military History of the Civil War. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780691169408.