This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islam in Iran |

|---|

|

| History of Islam in Iran |

| Scholars |

| Sects |

| Culture |

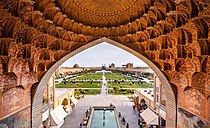

| Architecture |

| Organizations |

|

|

Traditionally, the thought and practice of Islamic fundamentalism and Islamism in the nation of Iran has referred to various forms of Shi'i Islamic religious revivalism[note 1] that seek a return to the original texts and the inspiration of the original believers of Islam. Issues of importance to the movement include the elimination of foreign, non-Islamic ideas and practices from Iran's society, economy and political system.[3][4] It is often contrasted with other strains of Islamic thought, such as traditionalism, quietism and modernism.[5] In Iran, Islamic fundamentalism and Islamism is primarily associated with the thought and practice of the leader of the Islamic Revolution and founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini ("Khomeinism"), but may also involve figures such as Fazlullah Nouri, Navvab Safavi, and successors of Khomeini.

In the 21st century, "fundamentalist" in the Islamic Republic of Iran generally refers to the political faction known as the "Principlists", (also spelled principlist) or Osoulgarayan[6]—as in acting politically based on principles of the Islamic Revolution[7][8][9]—which is an umbrella term for a variety of conservative circles and parties that (as of 2023) dominates politics in the country. (The Supreme Leader and the president are principalists, and principalists have control of the Assembly of Experts, the Guardian Council, the Expediency Discernment Council, and the Judiciary.)[10] The term contrasts with "reformist" or Eslaah-Talabaan, who seek religious and constitutional reforms.

- ^ Scheherezade Faramarzi, Iran’s Salafi Jihadis, Atlantic Council. May 17, 2018, quoted in Asadzade, Peyman (17 March 2022). "The Challenges and Advances of Iranian Sunnis". Manara magazine. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Aman, Fatemeh (21 March 2016). "Iran's Uneasy Relationship with its Sunni Minority". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Roy, Failure of Political Islam, 1994: p. viii

- ^ "Islamism – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ M. Hope and J. Young, CrossCurrents:ISLAM AND ECOLOGY. Retrieved 28 January 2007. dead link

- ^ Kevan Harris (2017). A Social Revolution: Politics and the Welfare State in Iran. Univ of California Press. p. 157. ISBN 9780520280816.

This discourse was eventually tagged with the Persian neologism osulgarāi, a word that can be translated into English as "fundamentalist", since "osul" means "doctrine", "root", or "tenet". According to several Iranian journalists, state-funded media were aware of the negative connotation of this particular word in Western countries. Preferring not to be lumped in with Sunni Salafism, the English-language media in Iran opted to use the term "principlist", which caught on more generally.

- ^ "Global Politician – Core members of Iran's council of Economic Governance". Globalpolitician.com. Archived from the original on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ^ "Hardliners seek consensus to defeat Rafsanjani". Daily Times. Pakistan. 9 June 2005. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ^ Axworthy, Michael (2016), Revolutionary Iran: A History of the Islamic Republic, Oxford University Press, p. 430, ISBN 9780190468965

- ^ SHAUL, BAKHASH (12 September 2011). "Iran's Conservatives: The Headstrong New Bloc". Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Tehran Bureau. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).