| Libellus responsionum | |

|---|---|

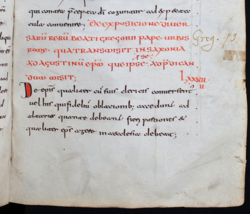

The beginning of the Libellus responsionum in an eighth-century canon law manuscript (Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, HB VI 113, fol. 166r) | |

| Full title | Libellus responsionum |

| Also known as | Responsiones; Responsa; JE 1843; "Per dilectissimos filios meos" |

| Author(s) | Pope Gregory I |

| Language | Latin |

| Date | ca 601 |

| Authenticity | presumed authentic |

| Manuscript(s) | over 150 |

| Principal manuscript(s) | Brussels, Bibliothèque royale Albert 1er, MS 10127–44 (363); Cologne, Erzbischöfliche Diözesan- und Dombibliothek, Codex 91; Copenhagen, Kongelige Bibliotek, Gl. kgl. Sam. 1595 (4°); Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, S.33 sup.; Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 14780, fols 1–53; Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 1603; Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 3846; Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 12444 ; Prague, Knihovna metropolitní kapituli, O. LXXXIII (1668), fols 131–45; Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, HB.VI.113; Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Codex lat. 2195, ff. 2v–46 |

The Libellus responsionum (Latin for "little book of answers") is a papal letter (also known as a papal rescript or decretal) written in 601 by Pope Gregory I to Augustine of Canterbury in response to several of Augustine's questions regarding the nascent church in Anglo-Saxon England.[1] The Libellus was reproduced in its entirety by Bede in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, whence it was transmitted widely in the Middle Ages, and where it is still most often encountered by students and historians today.[2] Before it was ever transmitted in Bede's Historia, however, the Libellus circulated as part of several different early medieval canon law collections, often in the company of texts of a penitential nature.

The authenticity of the Libellus (notwithstanding Boniface's suspicions, on which see below) was not called into serious question until the mid-twentieth century, when several historians forwarded the hypothesis that the document had been concocted in England in the early eighth century.[3] It has since been shown, however, that this hypothesis was based on incomplete evidence and historical misapprehensions. In particular, twentieth-century scholarship focused on the presence in the Libellus of what appeared to be an impossibly lax rule regarding consanguinity and marriage, a rule that (it was thought) Gregory could not possibly have endorsed. It is now known that this rule is not in fact as lax as historians had thought, and moreover that the rule is fully consistent with Gregory's style and mode of thought.[4] Today, Gregory I's authorship of the Libellus is generally accepted.[5] The question of authenticity aside, manuscript and textual evidence indicates that the document was being transmitted in Italy by perhaps as early as the beginning of the seventh century (i.e. shortly after Gregory I's death in 604), and in England by the end of the same century.

- ^ The Libellus is sometime designated as JE 1843, and/or by its incipit "Per dilectissimos filios meos". See P. Jaffé, Regesta pontificum Romanorum ab condita ecclesia ad annum post Christum natum MCXCVIII, 2 vols, second edition, eds F. Kaltenbrunner (to a. 590), P. Ewald (to a. 882), S. Löwenfeld (to a. 1198) (Leipzig, 1885–1888), no. 1843. It is edited by P. Ewald and L.M. Hartmann in Gregorii I papae Registrum epistolarum, 2 vols, MGH Epp. 1–2 (Berlin, 1891–1899), vol. II, pp. 332–43 (no. 11.56a).

- ^ P. Meyvaert, "Bede’s text of the Libellus responsionum of Gregory the Great to Augustine of Canterbury", in England before the Conquest: studies in primary sources presented to Dorothy Whitelock, eds P. Clemoes and K. Hughes (Cambridge, 1971), pp. 15–33.

- ^ See, most importantly, S. Brechter, Die Quellen zur Angelsachsenmission Gregors des Großen: Eine historiographische Studie, Beiträge zur Geschichte des alten Mönchtums und des Benediktinerordens 22 (Munster, 1941), and M. Deanesly and P. Grosjean, "The Canterbury edition of the answers of Pope Gregory I to Augustine", in The journal of theological studies 10 (1959), 1–49. For a review of scholarship that has challenged Gregory's authorship see M. D. Elliot, "Boniface, Incest, and the Earliest Extant Version of Pope Gregory I’s Libellus responsionum (JE 1843)", in Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte: Kanonistische Abteilung 100 (2014), pp. 62–111, at pp. 62–73.

- ^ K. Ubl, Inzestverbot und Gesetzgebung: die Konstruktion eines Verbrechens (300–1100), Millennium-Studien 20 (Berlin, 2008), pp. 219–51; Elliot, "Boniface, Incest, and the Earliest Extant Version", pp. 73–96.

- ^ P. Meyvaert, "Diversity within unity, a Gregorian theme", in The Heythrop journal 4 (1963), pp. 141–62; B. Müller, Führung im Denken und Handeln Gregors des Grossen, Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum 57 (Tübingen, 2009), pp. 341–62.