| Part of a series on |

| The Holocaust |

|---|

|

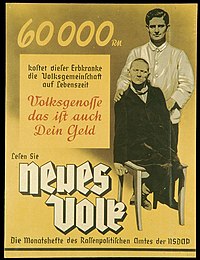

The phrase "life unworthy of life" (German: Lebensunwertes Leben) was a Nazi designation for the segments of the populace which, according to the Nazi regime, had no right to live. Those individuals were targeted to be murdered by the state via involuntary euthanasia, usually through the compulsion or deception of their caretakers. The term included people with disabilities and later those considered grossly inferior according to the racial policy of Nazi Germany. This concept formed an important component of the ideology of Nazism and eventually helped lead to the Holocaust.[1] It is similar to but more restrictive than the concept of Untermensch, subhumans, as not all "subhumans" were considered unworthy of life (Slavs, for instance, were deemed useful for slave labor).

The involuntary euthanasia program was officially adopted in 1939 and came through the personal decision of Adolf Hitler. It grew in extent and scope from Aktion T4 (which ended officially in 1941 when public protests stopped the program), through the Aktion 14f13 against concentration camp inmates.[2] The "euthanasia" of certain cultural and religious groups and those with physical and mental disabilities continued more discreetly until the end of World War II. The methods used initially at German hospitals such as lethal injections and bottled gas poisoning were expanded to form the basis for the creation of extermination camps where cyanide gas chambers were purpose-built to facilitate the extermination of the Jews, Romani, communists, anarchists, and political dissidents.[3]: 31 [4][5]

Historians estimate that 200,000 to 300,000 people were murdered under this program in Germany and occupied Europe.[6][7][8][a]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Liftonwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Ley, Astrid (2021). "Krankenmord im Konzentrationslager: Die "Aktion 14f13"". "Euthanasie" und Holocaust. Brill Schöningh. pp. 195–210. doi:10.30965/9783657791880_009. ISBN 978-3-657-79188-0. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Gypsieswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Henry Friedlander (1995), The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. University of North Carolina Press. September 1997. p. 163. ISBN 9780807846759.

- ^ Evans, Suzanne E. (January 2004). Forgotten crimes: the Holocaust and people with disabilities. Ivan R. Dee. p. 93. ISBN 1566635659.

- ^ "Exhibition catalogue in German and English" (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Memorial for the Victims of National Socialist ›Euthanasia‹ Killings. 2018.

- ^ "Euthanasia Program" (PDF). Yad Vashem. 2018.

- ^ a b Chase, Jefferson (26 January 2017). "Remembering the 'forgotten victims' of Nazi 'euthanasia' murders". Deutsche Welle.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).