This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (March 2008) |

Mittelafrika (German: [ˈmɪtl̩ˌʔaːfʁika], "Middle Africa") is the name created for a geostrategic region in central and east Africa. Much like Mitteleuropa, it articulated Germany's foreign policy aim, prior to the First World War, of bringing the region under German domination. The difference being that Mittelafrika would presumably be an agglomeration of German colonies in Africa, while Mitteleuropa was conceptualised as a geostrategic buffer zone between Germany and Imperial Russia to be filled with puppet states.

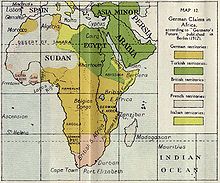

German strategic thinking was that if the region between the colonies of German East Africa (Rwanda, Burundi, and Tanganyika (Tanzania minus the island of Zanzibar)), German South West Africa (Namibia minus Walvis Bay), and Kamerun (today's Republic of Cameroon) could be annexed, a contiguous entity could be created covering the breadth of the African continent from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. Given the richness in natural resources of the Congo Basin alone, this region would accrue considerable wealth to the colonising power through the exploitation of natural resources, as well as contributing to another German aim of economic self-sufficiency.

The concept dates back to the 1890s, when the then Chancellor of Germany, Leo von Caprivi, gained the Caprivi Strip in the Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty. This addition to German South-West Africa attached the colony to the Zambezi River. The British and German empires competed for control over the region which now comprises Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi. South Africa-based businessman Cecil Rhodes, on behalf of the British government, established a colony in the latter region (named Rhodesia, after Rhodes himself). Germany also discussed with Britain for them to press their ally, Portugal, to cede their colonies of Angola and Mozambique to them. The British, however, had preferential trade agreements with Portugal, who they had long been allied with; though plans for an eventual Anglo-German partition of the Portuguese colonial empire were created, Britain would see its position in Africa severely weakened if they were applied, since the Germans could then effectively threaten their planned "Cape to Cairo Road". These plans were arguably made to be used only as a last resort to appease Germany in case she threatened to disrupt the balance of power in Europe. However, since German foreign policy interests were in subsequent years mainly directed at gaining mastery in Europe itself, and not in Africa, they were eventually shelved. Indeed, as it is likely that German concepts of a Mittelafrika were designed to put pressure on Britain to tolerate growing German dominance in the European continent, and not the other way around, colonial concessions would never placate the German Empire, as British politicians came to realise at the time.

The German aspiration of establishing a Mittelafrika were incorporated into Germany's aims in the First World War insofar as Germany expected to be able to gain the Belgian Congo if it were to defeat Belgium in Europe. The full realisation of Mittelafrika depended on a German victory in the European theatre of the First World War, where Britain would be forced to negotiate and cede its colony of Rhodesia to Germany when faced with a German-dominated continent across the English Channel. In the course of the actual war, German aspirations in Mittelafrika were never matched by events in the African theatre of the First World War. The German colonies were at very different levels of defence and troop strength when the war began in Europe, and were not in a position to fight a war due to a lack of material.