Modern Gothic, also known as Reformed Gothic, was an Aesthetic Movement style of the 1860s and 1870s in architecture, furniture and decorative arts, that was popular in Great Britain and the United States. A rebellion against the excessive ornament of Second Empire and Rococo Revival furniture, it advocated simplicity and honesty of construction, and ornament derived from nature. Unlike the Gothic Revival, it sought not to copy Gothic designs, but to adapt them abstract them, and apply them to new forms.[1]

The style's leading advocates were English designers Christopher Dresser and Charles Eastlake. Eastlake's Hints on Household Taste, Upholstery, and Other Details, published in England in 1868 and in the United States in 1872, was one of the most influential decorating manuals of the Victorian Era. The Eastlake movement argued that furniture and decor in people's homes should be made by hand or by machine-workers who took personal pride in their work. Eastlake lectured in the United States in 1876.

French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc advocated similar principles in Entretiens sur l'architecture (in 2 volumes, 1863–72), which was translated and published in the United States as Discourses on Architecture (1875). He incorporated modern materials, such as cast iron, into his historicist designs and building restorations. He also designed furniture.

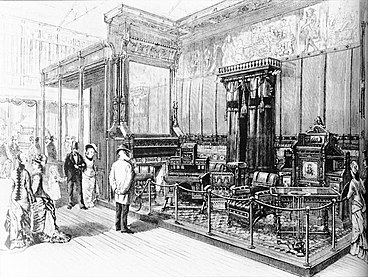

Other designers who worked in the Modern Gothic style include Bruce James Talbert, Edward William Godwin, and Thomas Jeckyll in England; and Kimbel and Cabus, Frank Furness, and Daniel Pabst in the United States. The style's parting zenith was the Modern Gothic furniture exhibited at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.[2]

By 1878, the American critic Clarence Cook was already pronouncing the style passé:

There was a little while ago quite a rage for a certain style of furniture that made a great display of seeming steel hinges, key-plates, and handles, with inlaid tiles, carving of an ultra-Gothic type, and an appearance of the ingenuous truth-telling in the construction. The chairs, tables and bedsteads looked as if they had been on the dissecting-table and flayed alive,—their joints and tendons displayed to an archaeologic and unfeeling world. One particular firm [Kimbel and Cabus] introduced this style of furniture, and, for a time, had almost the monopoly of it. It had a great run.[3]

-

Clock (c. 1865), designed by Bruce James Talbert, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, Indiana.

-

Sideboard (1867), designed by Bruce James Talbert.

-

Sideboard (1868), designed by Thomas Jeckyll, Wolfsonian-FIU Museum, Miami Beach, Florida.

-

Bookcase (1869), designed by Edward William Godwin, Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

-

Cabinet doors (1871), designed by Frank Furness, made by Daniel Pabst.

-

Thomas Hockley House (1875), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Frank Furness, architect.

-

Campeche-style chair (c. 1875–1880), attributed to Frank Furness and Daniel Pabst.

-

Secretary-abattant (c. 1875), by Kimbel and Cabus.

-

Kimbel and Cabus exhibit at the 1876 Centennial Exposition.

-

Cover of Harper's Weekly, October 14, 1876.

-

Settle (c. 1878), designed by Viollet-le-Duc, Musée du Second Empire, Compiègne, France.

-

Bedstead (1880), by Herter Brothers, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia.

- ^ Sarah E. Kelly, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, vol. 32, no. 1 (2006), p. 18.

- ^ Burke, Doreen Bolger, ed. (1986). In Pursuit of Beauty: Americans and the Aesthetic Movement. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 446. ISBN 978-0-87099-468-5.

- ^ Clarence Cook, The House Beautiful: Essays on Beds and Tables, Stools and Candlesticks, (New York: Scribner, Armstrong and Company, 1878), p. 325.