| Nanjing Massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of Nanking | |

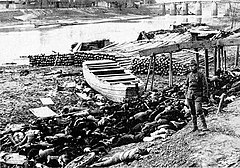

A Japanese soldier pictured with the corpses of Chinese civilians by the Qinhuai River | |

| Location | Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, Republic of China |

| Date | From December 13, 1937, for six weeks[note 1] |

Attack type | Mass murder, wartime rape, looting, torture, arson |

| Deaths | 200,000 civilians (consensus),[1] estimates range from 40,000 to over 300,000 |

| Victims | 20,000 to 80,000 women and children raped, 30,000 to 40,000 POWs executed (another 20,000 male civilians falsely accused of being soldiers executed) |

| Perpetrators | Imperial Japanese Army

|

| Motive | |

| This article is part of the series on the |

| Nanjing Massacre |

|---|

| Japanese war crimes |

| Historiography of the Nanjing Massacre |

| Films |

| Books |

| History of the Republic of China |

|---|

|

|

|

The Nanjing Massacre[2] or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as Nanking[note 2]) was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the Battle of Nanking and the retreat of the National Revolutionary Army in the Second Sino-Japanese War, by the Imperial Japanese Army.[3][4][5][6] Beginning on December 13, 1937, the massacre lasted six weeks.[note 1] The perpetrators also committed other war crimes such as mass rape, looting, torture, and arson. The massacre is considered to be one of the worst wartime atrocities.[8][9][10]

The Japanese army had pushed quickly through China after capturing Shanghai in November 1937. As the Japanese marched on Nanjing, they committed violent atrocities in a terror campaign, including killing contests and massacring entire villages.[11] By early December, their army had reached the outskirts of Nanjing.

The Chinese army withdrew the bulk of its forces since Nanjing was not a defensible position. The civilian government of Nanjing fled, leaving the city under the de facto control of German citizen John Rabe, who had founded the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone. On December 5, Prince Yasuhiko Asaka was installed as Japanese commander in the campaign. Whether Asaka ordered the massacre is disputed, but he took no action to stop the massacre.

The massacre officially began on December 13, the day Japanese troops entered the city after a ferocious battle. They rampaged through Nanjing almost unchecked. Captured Chinese soldiers were summarily executed in violation of the laws of war, as were numerous male civilians falsely accused of being soldiers. Rape and looting were widespread. Due to multiple factors, death toll estimates vary from 40,000 to over 300,000, with rape cases ranging from 20,000 to over 80,000 cases. However, most scholars support the validity of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East and its findings, which estimate at least 200,000 murders and at least 20,000 cases of rape. The massacre finally wound down in early 1938. John Rabe's Safety Zone was mostly a success, and is credited with saving at least 200,000 lives. After the war, multiple Japanese military officers and Kōki Hirota, former Prime Minister of Japan and foreign minister during the atrocities, were found guilty of war crimes and executed. Some other Japanese military leaders in charge at the time of the Nanjing Massacre were not tried only because by the time of the tribunals they had either already been killed or committed seppuku (ritual suicide). Prince Asaka, as part of the Imperial Family, was granted immunity and never tried.

The massacre remains a wedge issue in Sino-Japanese relations. Historical revisionists and nationalists as well as many government officials in Japan have either denied or minimized the massacre.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Library of Congress, ed. (November 1948). Judgment International Military Tribunal for the Far East The Pacific War (PDF). p. 1015.

- ^ (simplified Chinese: 南京大屠杀; traditional Chinese: 南京大屠殺; pinyin: Nánjīng Dàtúshā, Japanese: 南京大虐殺, romanized: Nankin Daigyakusatsu)

- ^ "International Memory of the World Register Documents of Nanjing Massacre" (PDF). UNESCO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Smalley, Martha L. (1997). American Missionary Eyewitnesses to the Nanking Massacre, 1937-1938. Connecticut: Yale Divinity Library Occasional Publications. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Chang, Iris. 1997. The Rape of Nanking. p. 6.

- ^ Lee, Min (31 March 2010). "New film has Japan vets confessing to Nanjing rape". Salon.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 31 October 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ Library of Congress, ed. (1964–1974). "29 July 1946. Prosecution's Witnesses. Bates, Miner Searle". Record of proceedings of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. pp. 2631, 2635, 2636, 2642–2645. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Yamamoto M. 2000was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Awas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Fogel 2000, p. backcover.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:5was invoked but never defined (see the help page).